Pages

Saturday, February 28, 2009

Lama Sabachthani

Morris Kestelman 1905-1998

Morris Kestelman 1905-1998Lama Sabachthani [Why have you forsaken me?] 1943

Oil on canvas

Imperial War Museum, London

Kestelman was the son of European Jewish immigrants and he was brought up in the East end of London.

His philosophy of art was always "to revel in the sunny side of life . . . heaven knows we all need the solace we can get from art."

However in the early 1940s, during the Second World War, the scale of the Nazi genocide of the Jewish race was gradually becoming apparent.

The above painting is the artist`s response to the news from the Continent.

The impact of the news was keenly felt in many quarters of British society.

Various policy prescriptions were advanced to try to aid the plight of the Jew in Europe. None seemed to attract much support. The following are links to the Debates in the House of Commons and House of Lords in 1943, when the question was discussed. From them one gets an idea of the context of the times in which the painting was executed:

HC Deb 19 May 1943 vol 389 cc1117-204 1117 : Refugee Problem

House of Lords Debate:Refugee Problem: Deb 28 July 1943 vol 128 cc836-72

The painting depicts a scene of mourning: a group of Jewish men, women and children weep and mourn over a mound of corpses.

The title is taken from the opening verse of Psalm 22: My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

These of course were the last words of Christ on the Cross

The psalm starts with a declaration that the psalmist has been deserted by God.

There is then a complex dialogue that restates the omnipotence of God and yet also elucidates present torment and anguish. The psalmist meditates on the possibility that God might not rescue, and applied to this context where intervention seemed neither feasible nor imminent, it questions the very rule and presence of God. But the psalm ends on a positive note: the triumph of God over evil and injustice.

Psalm 22

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are you so far from saving me,

so far from the words of my groaning?

2 O my God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer,

by night, and am not silent.

3 Yet you are enthroned as the Holy One;

you are the praise of Israel.

4 In you our fathers put their trust;

they trusted and you delivered them.

5 They cried to you and were saved;

in you they trusted and were not disappointed.

6 But I am a worm and not a man,

scorned by men and despised by the people.

7 All who see me mock me;

they hurl insults, shaking their heads:

8 "He trusts in the LORD;

let the LORD rescue him.

Let him deliver him,

since he delights in him."

9 Yet you brought me out of the womb;

you made me trust in you

even at my mother's breast.

10 From birth I was cast upon you;

from my mother's womb you have been my God.

11 Do not be far from me,

for trouble is near

and there is no one to help.

12 Many bulls surround me;

strong bulls of Bashan encircle me.

13 Roaring lions tearing their prey

open their mouths wide against me.

14 I am poured out like water,

and all my bones are out of joint.

My heart has turned to wax;

it has melted away within me.

15 My strength is dried up like a potsherd,

and my tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth;

you lay me in the dust of death.

16 Dogs have surrounded me;

a band of evil men has encircled me,

they have pierced my hands and my feet.

17 I can count all my bones;

people stare and gloat over me.

18 They divide my garments among them

and cast lots for my clothing.

19 But you, O LORD, be not far off;

O my Strength, come quickly to help me.

20 Deliver my life from the sword,

my precious life from the power of the dogs.

21 Rescue me from the mouth of the lions;

save me from the horns of the wild oxen.

22 I will declare your name to my brothers;

in the congregation I will praise you.

23 You who fear the LORD, praise him!

All you descendants of Jacob, honor him!

Revere him, all you descendants of Israel!

24 For he has not despised or disdained

the suffering of the afflicted one;

he has not hidden his face from him

but has listened to his cry for help.

25 From you comes the theme of my praise in the great assembly;

before those who fear you will I fulfill my vows.

26 The poor will eat and be satisfied;

they who seek the LORD will praise him—

may your hearts live forever!

27 All the ends of the earth

will remember and turn to the LORD,

and all the families of the nations

will bow down before him,

28 for dominion belongs to the LORD

and he rules over the nations.

29 All the rich of the earth will feast and worship;

all who go down to the dust will kneel before him—

those who cannot keep themselves alive.

30 Posterity will serve him;

future generations will be told about the Lord.

31 They will proclaim his righteousness

to a people yet unborn—

for he has done it.

Thursday, February 26, 2009

A Papal Procession 1846 (8th November 1846)

Giovanni Olivieri

Esatta relazione della cavalcata con la quale la santita` di N.S. Papa Pio IX si porto` a prendere il solenne possesso della basilica lateranense e delle ceremonie che in essa seguirono il giorno 8 novembre 1846./Description of the procession of Pope Pio IX on 8 November 1846, to the Basilica di S. Giovanni in Laterano. (1846)

21, [3] p., [1] folded leaf of plates ill. 19 cm. with engravings

Does history repeat itself ?

Blame seems to be presntly heaped on one Scottish banker in particular.

This of course is not the first time that Scottish bankers have caused problems on a large scale.

Sir William Paterson (born April, 1658 in Tinwald, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland - died in Westminster, London, on 22 January 1719) after helping to found The Bank of Scotland and The Bank of England led Scotland into theinfamous Darien scheme, which in effect bankrupted the then Scottish economy,leading to the Act and Treaty of Union of 1707.

Even more famous or infamous, is John Law (bap. 21 April 1671 – 21 March 1729)

In August 1717, he bought the Mississippi Company, to help the French colony in Louisiana.He helped found the Compagnie Perpetuelle des Indes on 23 May 1719 and eventually became head of effectively the Central bank of France. In 1720 the bank and company were united and Law was appointed Controller General of Finances to attract capital. Speculation in the shares and lack of proper capitalisation caused the company's two branches, the trading arm and the bank arm, to collapse simultaneously. The economic crisis not only affected France but the whole of WEstern Europe.

By the end of 1720 he was dismissed and eventually died in poverty in Venice in 1729.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Ash Wednesday

François Marius Granet 1775-1849

François Marius Granet 1775-1849La cérémonie des cendres dans une église de Rome/ The ceremony of distributing ashes in a church in Rome 1844

Pen, black pencill, brown ink, aquarelle 24cm x 37cm

Musée du Louvre département des Arts graphiques, Paris

Granet`s most famous painting is of Capuchins celebrating Mass in Rome. Ingres was jealous of him

His subjects were of historical or romantic interest.

This drawing of a contemporary scene is of historical interest: a ceremony taking place over 160 years ago and still taking place today.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Carnevale ... at Viareggio (Tuscany)

Monday, February 23, 2009

The Chair of St Peter

The Cathedra Petri or Chair of Saint Peter is the chair preserved in St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, enclosed in a gilt bronze casing that was designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and executed 1647–53.

It is the symbol of the authority of the Bishop of Rome and of his primacy in the Church.

The reliquary by Bernini is also in the shape of a chair

The chair encased in the reliquary was given by Charles the Bald to Pope John VIII in AD 875.

Its medieval simplicity is reminiscent of the Coronation Chair of the British monarch in Westminster Abbey.

Riveted by Saint Mark’s Gospel

Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, circa 1431 - Mantua, 1506)

Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, circa 1431 - Mantua, 1506)St Mark

1447 - circa 1448

Canvas; H. 82 cm; W. 63.7 cm

Frankfurt, Städelsches Kunstinstitut

Monsignor Roderick Strange, the Rector of the Pontifical Beda College, Rome, recently wrote about reading the Gospel of St Mark.

"Almost thirty years ago I spent a memorable night at the Oxford Playhouse. The stage was bare except for a table and chair. As the performance began, Alec McCowen walked on and placed a copy of the King James’ Bible on the table, in case, he remarked with self-deprecating humour, he forgot his lines. And then he began to recite the Gospel according to St Mark. It was spellbinding. We may be familiar with much of the text, but probably from hearing passages read out in church, as they will often be this year; but to hear the text whole was another experience altogether.

More recently I read the text straight through again in a single sitting. It took me about two hours. Once more the experience was riveting. I would encourage anyone, whether Christian or not, to do the same. The text as a whole has a power we may miss when pondering just particular passages or sections.

In the beginning there is an urgency, stirred by the expression, “and immediately”, as Jesus is baptised, and immediately goes into the wilderness, and immediately calls disciples, and immediately preaches in Capernaum, and immediately cures the sick. These words recur 13 times in the early verses, a refrain which injects movement and energy into the action.

Then there are questions, “why are you eating with tax collectors and sinners?”, “why aren't you fasting?”, “why are you breaking the Sabbath?”, questions which are handled with lightness and humour, an effect lost when a passage is just proclaimed solemnly in church. I like particularly the story of the man with the withered hand who is cured in the synagogue on the Sabbath. He hadn’t come to be healed, just to say his prayers. Invited to stretch out his hand, I suppose at first he stretched out his good one. “No, not that one, the other,” he would have been told. Imagine his jaw dropping when he lifts what was withered and finds it strong again.

There are parables and cures. People are amazed. Then halfway through, Jesus asks the crucial question, “Who do you say I am?” And Peter replies, “You are the Christ.”

It is the hub of the drama. The mood shifts. The atmosphere becomes more sombre. Predictions follow about Jesus’s passion, and conversations with a rich young man, with the Sons of Zebedee, and with blind Bartimaeus begin to alert us to the demands of discipleship. They are costly, but to follow with faith like Bartimaeus allows us to see.

After entering Jerusalem, Jesus drives from the Temple precincts those who had set up shop there. He is challenged about his authority to act as He is doing, about paying taxes to Caesar, and about the Resurrection.

The force of his replies dumbfounds his challengers, and after He has explained that the greatest commandment is to love God and our neighbour, no one dares to question him further.

Then he takes the offensive, asking why David called the Christ Lord, criticising the self-regard of the scribes, praising the generosity of a poor widow, and predicting the destruction of the Temple. It is not hard to see why those He challenged opposed Him.

Then events begin to move swiftly. Judas Iscariot goes to the chief priests to lay plans for his betrayal. During a supper with the 12 Disciples, which proves to be his last, Jesus identifies Himself with the bread they break and the cup they share: “This is my body, and this is my blood.” Afterwards, he is arrested in Gethsemane and taken to be tortured and tried. From the Cross only one word is spoken, a cry of desolation, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The moment is dark and he dies.

Later, after the Sabbath, when women go to anoint the hastily buried body, they find the tomb empty, but a young man, dressed in white, tells them that Jesus has risen and they are to tell the Disciples, but they run away, filled with fear.

And so the text ends. A later ending tells of Jesus meeting the Disciples, instructing them, and ascending into Heaven, but the earlier text stops there, in fear and bewilderment, the greatest cliffhanger ending of all.

Revisit the text. We still have much to learn."

Sunday, February 22, 2009

La Berceuse

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)La Berceuse (Woman Rocking a Cradle; Augustine-Alix Pellicot Roulin, 1851–1930), 1889

Oil on canvas; 36 1/2 x 29 in. (92.7 x 73.7 cm)

Signed and dated (on arm of chair): vincent / arles 89; inscribed (lower right): La / Berceuse

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Augustine Roulin, 1851–1930, was the wife of his friend, Joseph Roulin, the postmaster of Arles

Van Gogh painted five versions of this theme shortly before his self-mutilation and final break with Gauguin. It was completed after he left hospital.

Augustine, Joseph and their children became for Van Gogh an image of robust, familial warmth.

He said it was a picture that might console fishermen far out at sea in a storm. Instead of being thrown about by the ocean, they would feel they were being rocked in a cradle and remember their own childhood lullabies.

Although Van Gogh regarded it as a work of religious art, his categorisation of it as such cannot be sustained.

It is an allegory of motherhood. It is a sad and poignant reminder of the suffering which Van Gogh sustained and endured at a particularly difficult time of his life.

Hatchet Job

It is an attack on Fr Finigan who writes the excellent blog The Hermeneutic of Continuity.

In Responding to the Tablet Father Finigan sets out the article in full and his response.

The offending article is riddled with inaccuracy and false innuendo.

I believe the term for such an article is "hatchet job".

The personal attack on Fr Finegan in The Tablet is really beyond the pale.

Whatever one may think about the Missal of Blessed John XXIII, it is a valid option for a parochial Mass. As such the celebration of one such Mass out of a total of four for the Sunday obligation is certainly not excessive.

The objectionable parts of the article in The Tablet which should be the cause of serious concern are:

1. The article would only widen divisions in the parish when the Bishop is still in the process of trying to mediate betwen the parties to produce an amicable resolution of the various issues.

2. The clear partisan nature of the piece. Father Finegan`s defence of his position is dismissed in one sentence as a thirty seven page essay. Thre is no attempt to briefly summarise his position.

3. The subtle and not so subtle innuendoes about the personal character and actions of Father Finegan: in particular in relation to the use of Church funds (vestments, no published accounts); his so called "martinet" charater (the issuing of "rules" regarding silence in Church).

It does seem that Father Finegan has been the subject of a totally unjustified and malicious personal attack.

One does not expect to see such an article of such a nature in a Catholic magazine which is given wide circulation through free distribution channels of Catholic parishes. Ideology seems to have overriden the quest for truth and the other values which we expect from a journal which proclaims itself to be "Catholic".

One does wonder if the writer of the piece had seriously considered the adverse effects of writing such a piece on the participants to the dispute. Of course, the writer can simply disappear after writing the piece. She does not have to pick up the pieces and restore a Catholic community. She may have probably widened the dispute, perhaps irretrievably.

There is a lack of vocations. There is a diminishing number of priests. Such an article can only reduce morale among the existing priests. We should encourage good priests not subject them to public ridicule and scorn.

As well as complaining to the trustees of The Tablet, should parish priests not reconsider whether they should continue to stock issues of The Tablet in their churches while the offending article continues to stand on the record without contradiction ?

Friday, February 20, 2009

Found Drowned

George Frederick Watts RA (1817-1904).

George Frederick Watts RA (1817-1904).Found Drowned 1867

Oil on canvas.

The Watts Gallery, Compton. (presently exhibited at The Guildhall Art Gallery, London)

The title is taken from the gloomy daily column in the The Times which published lists of women, mostly prostitutes, found dead in the Thames

It seems that his painting was based on Thomas Hood's (1799-1845) poem the "Bridge of Sighs."

It is perhaps too "Victorian", melodramatic and didactic for modern tastes.

Note the religious symbolism: the cross pose of the woman; the star above the woman; the light which shines on her body

'Right to die' can become a 'duty to die'

In the Telegraph he has written of the experience of Oregon and its "assisted suicide" law.

"Imagine that you have lung cancer. It has been in remission, but tests show the cancer has returned and is likely to be terminal. Still, there is some hope. Chemotherapy could extend your life, if not save it. You ask to begin treatment. But you soon receive more devastating news. A letter from the government informs you that the cost of chemotherapy is deemed an unjustified expense for the limited extra time it would provide. However, the government is not without compassion. You are informed that whenever you are ready, it will gladly pay for your assisted suicide.

Think that's an alarmist scenario to scare you away from supporting "death with dignity"? Wrong. That is exactly what happened last year to two cancer patients in Oregon, where assisted suicide is legal.

Barbara Wagner had recurrent lung cancer and Randy Stroup had prostate cancer. Both were on Medicaid, the state's health insurance plan for the poor that, like some NHS services, is rationed. The state denied both treatment, but told them it would pay for their assisted suicide. "It dropped my chin to the floor," Stroup told the media. "[How could they] not pay for medication that would help my life, and yet offer to pay to end my life?" (Wagner eventually received free medication from the drug manufacturer. She has since died. The denial of chemotherapy to Stroup was reversed on appeal after his story hit the media.)

Despite Wagner and Stroup's cases, advocates continue to insist that Oregon proves assisted suicide can be legalised with no abuses. But the more one learns about the actual experience, the shakier such assurances become.

At a meeting in the House of Commons on Monday night hosted by the anti-euthanasia charity Alert and Labour MP Brian Iddon, I hope to bring home to MPs and the British public just how dangerous it would be to legalise euthanasia. The Oregon experiment shows how easily the "right to die" can become a "duty to die" for vulnerable and depressed people fearful of becoming a burden on the state or their relatives. I know that a powerful and emotive campaign is being waged in the UK media – using heart-rending cases such as multiple sclerosis sufferer Debbie Purdy – to inveigle Parliament into changing the law.

Miss Purdy, who lost in the Appeal Court on Thursday, wants to secure a legal guarantee that her husband would not be prosecuted if he accompanied her to the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland – one of the few places where euthanasia is legal. Much as I sympathise with her plight, such a guarantee would lure us on to the slippery slope where the old and the sick come under pressure to end their lives.

A study published in the Journal of Internal Medicine last year, for example, found that doctors in Oregon write lethal prescriptions for patients who are not experiencing significant symptoms and that assisted suicide practice has had little do with any inability to alleviate pain – the fear of which is a chief selling point for legalisation.

The report said that family members described loved ones who pursue "physician-assisted death" as individuals for whom being in control is important, who anticipate the negative aspects of dying and who believe the impending loss of self and quality of life will be intolerable. They fear becoming a burden to others, yet want to die at home. Concerns about what may be experienced in the future were substantially more powerful reasons than what they experienced at that point in time.

When a scared and depressed patient asks for poison pills and their doctor's response is to pull out the lethal prescription pad, it confirms the patient's worst fears – that they are a burden, that they are less worth loving. Hospices are geared to address such concerns. But effective hospice care is undermined when a badly needed mental health intervention is easily avoided via a state-sanctioned, physician-prescribed overdose of lethal pills.

Do the guidelines protect depressed people in Oregon? Hardly. The law does not require treatment when depression is suspected, and very few terminal patients who ask for assisted suicide are referred for psychiatric consultations. In 2008 not one patient who received a lethal prescription was referred by the prescribing doctor for a mental health evaluation.

As palliative care physician Dr Kathleen Foley and psychiatrist Herbert Hendin, an expert on suicide prevention, wrote in a scathing exposé of Oregon assisted suicide, physicians are able to "assist in suicide without inquiring into the source of the medical, psychological, social and existential concerns that usually underlie requests … even though this type of inquiring produces the kind of discussion that often leads to relief for patients and makes assisted suicide seem unnecessary."

Oregon has become the model for how assisted suicide is supposed to work. But for those who dig beneath the sloganeering and feel-good propaganda, it becomes clear that legalising assisted suicide leads to abandonment, bad medical practice and a disregard for the importance of patients' lives. "

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Sacred and Great

There you can download and read Sacred and Great, a short and concise paper on the Sacred Liturgy.

Its theme is Liturgy as a means not of division but as a means of celebrating that diversity which exists within the Church and being one of the central planks of ensuring mutual reconciliation, understanding and harmony within the Church.

Saint Bede the Venerable

The Tomb of the Venerable Bede in Durham Cathedral

The Tomb of the Venerable Bede in Durham Cathedral Cemented into the wall of the tower of St Paul`s Church in Jarrow, is the original stone slab which records in a Latin inscription the dedication of the church on 23 April AD 685, which would have been one of the churches known to St Bede. In AD 682, Ceolfrid its superior, left Wearmouth with 20 monks (including his protege the young Bede) to start the foundation in Jarrow.

Cemented into the wall of the tower of St Paul`s Church in Jarrow, is the original stone slab which records in a Latin inscription the dedication of the church on 23 April AD 685, which would have been one of the churches known to St Bede. In AD 682, Ceolfrid its superior, left Wearmouth with 20 monks (including his protege the young Bede) to start the foundation in Jarrow. In his General Audience of Wednesday 18th February 2009, the Pope spoke of Saint Bede the Venerable (672/673–May 26, 735).

He said:

"In our catechesis on the early Christian writers of East and West, we now turn to Saint Bede the Venerable. A monk of the monastery of Wearmouth in England, Bede became one of the most learned men of the early Middle Ages and a prolific author, while also gaining a reputation for great holiness and wisdom.

His scriptural commentaries highlight the unity of the Old and New Testaments, centred on the mystery of Christ and the Church.

Bede is best known, however, for his historical writings, in which he traced the history of the Church from the Acts of the Apostles, through the age of the Fathers and Councils, and down to his own times. His Ecclesiastical History recounts the Church’s missionary expansion and growth among the English people.

Bede’s rich ecclesial, liturgical and historical vision enable his writings to serve as a guide for the Church’s teachers, pastors and religious in living out their vocations in the service of the Church’s mission.

His great learning and the sanctity of his life, earned Bede the title of “Venerable”, while the rapid spread of his writings made him a highly influential figure in the building of a Christian Europe."

Monday, February 16, 2009

The Lion of Münster

Clemens August Cardinal Graf von Galen arriving back in Münster, Germany after receiving the Cardinal`s hat from Pope Pius XII in Rome in March 1946

For a brief life of Blessed Cardinal Graf von Galen (March 16, 1878 – March 22, 1946) and his three famous sermons against the Nazis, see here.

The speeches protested against the desecration of Catholic churches, the closing of convents and monasteries, and the deportation and euthanasia of mentally ill people (who were sent to destinations, usually concentration camps, while a notice was sent to family members stating that the person is question had died).

After having preached these sermons the Bishop was prepared to be arrested by the Gestapo. It was Reichsleiter Bormann who suggested to Hitler, that the Bishop should be taken into custody and be hanged.

The Nazi command, however, feared that in such a case the population of the diocese of Munster had to be written off as lost for the duration of the war.

The Bishop was deeply dejected when in his place 24 secular priests and 13 members of the regular clergy were deported into concentration camps, of whom 10 lost their lives.

In his speech to the crowds in Münster in 1946 after receiving the Cardinal`s hat , he said:

"Thousands of people felt painfully with me and like me that the truth of God and the justice of God, human dignity and the human rights were being set aside, despised and trampled on; with me and like me they felt it a bitter injustice also toward the true well-being of our people that the religion of Christ was hemmed in and ever more confined. I knew that many had suffered grievous wrong, very much more grievous than what I myself suffered personally, in the persecutions of truth and justice that we have been through.

They could not speak, they could only suffer. Perhaps in the eyes of God – for whom suffering, yes suffering, weighs much more than acting and speaking – and perhaps also many of those here now have in reality merited more in the sacred eyes of God, because they have suffered more than me.

But my right and my duty was to speak out and I spoke out, for you, for the countless persons gathered here, for the countless people of our beloved country of Germany, and God blessed my words, and your love and your fidelity, my beloved diocesans, kept me from what could have been my end, but perhaps they also prevented me from receiving the more beautiful reward, [in a voice choked with tears] the glorious crown of martyrdom.

Your fidelity prevented it. Because you were behind me, and the powerful knew that the people and the bishop in the diocese of Münster formed an unbreakable unity, and that, had they struck at the bishop, all the people would have felt stricken."

The epitaph engraved on his sepulchral monument is:

"Unfortunately, the conditions of the times strongly dissipate the effectiveness of the virtues of even the best of men"

Sunday, February 15, 2009

Historical monuments in time of war

Philip Alexius de László (1869-1937)

Philip Alexius de László (1869-1937)Archbishop Dr. Cosmo Lang, 1932

Oil on canvas, 165.8 x 108.6 cm

Corporation of the Church House

One of the criticisms of Pope Pius XII is that he did speak out about the Allied bombing of Italy and Rome in particular during the Second World War when he did not speak out or loudly enough about other subjects. The questions is: was it a topic which should have so exercised his mind ?

Of course, he was Bishop of Rome. That should have been enough answer. However some have insinuated that this indicated a degree of partiality on his part.

So just how important was the topic in the scheme of things at that time in the 1940s?

He was not the only religious figure to be concerned about the problem. It also exercised non-Catholics on the side of the Allies.

In the middle of the conflict on 16th February 1944, the former Archbishop of Canterbury (Lord Land of Lambeth)(31 October 1864 – 5 December 1945), (Archbishop of York (1908–1928) and, later, Archbishop of Canterbury (1928–1942)) initiated a debate in the House of Lords on this very topic: "the importance of preserving objects of special historical or cultural value within the theatres of war, and to ask His Majesty's Government what measures they have taken or propose to take for this purpose."

The debate is reported here.

Lord Lang in setting out the terms of the debate said:

"Think of Rome itself. Rome does not belong to Italy; it belongs to the world. It does not belong to any particular time; it belongs to all time. It justifies its title as the Eternal City. I need not remind your Lordships that it is the object of veneration by millions of our fellow Christians in all parts of the world. I notice that last week in the debate which your Lordships will remember, my noble friend Viscount FitzAlan, though he described himself as an out-and-out bomber, said that it would be deplorable both on religious grounds and also on cultural grounds if any damage were done to the city of Rome. It must have been a satisfaction to him to hear the assurance given him by my noble friend the Leader of the House, that it was not the intention of His Majesty's Government to drop bombs on the Vatican City nor so far as it could be avoided on the city of Rome. "

But it was not only destruction within Rome that caused him concern:

" But Rome does not stand by itself. I wonder whether anywhere in the world there is such a constellation of lovely cities, towns and villages as in the north of Italy, into which the devastating tide of war must sooner or later flow. May I venture to remind your Lordships of some of them and the great monuments in them? There is Assisi with its memories of St. Francis and the pictures of Giotto; Siena with its memories of St. Catherine and its lovely buildings; Florence, of which I need not speak because Florence abides in the memories of all who have seen it; Padua, Perugia, Pisa, Ravenna, retaining in the twentieth century in its mosaics the austere splendours of Bizantine art, and perhaps most of all, Venice, that Queen of Beauty enthroned on the seas. All these places are beautiful in themselves. Most of them contain treasures whose value it is impossible to measure. Must we not think with dismay of the possibility of any of these wonderful creations and expressions of the human spirit being damaged or destroyed by the ravages of war?"

He called for a sensible policy:

"On the one hand, there are those who ask impatiently, and rather contemptuously: "What is the worth of these dead stones and dead pictures in comparison with the life of one single soldier?" But these things are not dead. They are always alive; they have, as has been truly said, the quality of enhancing life, of giving fresh vitality to the mind and spirit of successive generations. And it must not be forgotten that they are part of that humane civilization which it is one of our aims, in this war, to protect against barbarians. On the other hand, there are those who, in their zeal for history and art, tend to forget the inexorable necessities of war. Just because the issues involved in the war are so great, just because it is being waged for the whole of civilization and not only for this aspect of it, just because from all the enslaved and oppressed countries a cry for liberation is rising, it is impossible to sanction anything that would seriously hinder the one essential thing—that the enemy, who is prepared to bring all this evil on the world, should be defeated rapidly and completely. It must never be allowed, for one moment, to be supposed by the enemy that if he chooses to occupy any of these centres of history or of art and to use them as posts for his own operations, he will be allowed to remain immune from attack."

He also raised the question of the attacks on Monte Cassino.

The debate attracted speeches critical of Lord Lang`s position. However Lord Lang`s position was supported by the Anglican Bishop of Birmingham who said:

"The noble and most reverend Lord, Lord Lang, has brought up to day the question of the cultural monuments of Italy, and especially those of the early Christian Renaissance. Such things as Giotto's tower at Florence and the great cathedrals at Siena and Assisi bind all Christians together. Too often in the past we have quarrelled with one another, but these magnificent buildings, some of the finest achievements of European civilization, are Christian, and we cannot forget it....

We are hoping against hope that somehow or another the Christian spirit will lead to an ending of this war otherwise than by complete collapse of the other side, for we look to a future when we must live in friendship with those who are now our enemies.

We wish a free Europe, but we wish also a Christian Europe.

I put this point of view. I know many of your Lordships think it is foolishness, and indeed it has been said that the ultimate outcome of that point of view is conscientious objection—Christian pacifism. Yes, but Christians for the first three centuries of the existence of the Christian Church adopted this policy of passive acceptance of wrong, and in the end, against the whole might of the Roman Empire, they won. Is it not possible that there are powers from on high who can join in the conflict, and that if we try to keep our ideals pure, if we do all that we can to avoid the implications of total war, we may yet find a help that at present we do not expect? "

It is clear from the Government`s response that they adopted the policy of General Eisenhower which was set out by the Lord Chancellor in the debate. The Government at least recognised the importance of historical monuments and the validity of the formr Archbishop`s concerns but when it came to assess these against the lives of Allied troops, the weight given to the lives of Allied troops would prevail.

Saturday, February 14, 2009

Christ in Glory

Duncan Grant (1885-1978) was the lead artist for the Berwick murals and put forward the initial proposals.

The mural depicts Christ, having offered himself on the cross, now enthroned in heaven with angels worshiping him.

On the right of the Chancel arch are Bishop Bell (kneeling) and behind him the Rector of Berwick, Revd G. Mitchell.

On the left are the kneeling figures of a soldier (Douglas Hemming, killed at Caen in 1944), a sailor (Mr Weller) and an airman (Mr Humphry).

Christ’s rule and victory over death is set over a country in the turmoil of a war. Poppies can be seen in the foreground symbolising remembrance and resurrection. The South Downs landscape is in the background.

Feibusch: The Drummer

"Fear was one of the themes of the times and a fundamental feeling for many people during the crises that shook the Weimar Republic after 1918. This angst increased from 1933 on during the Nazi dictatorship and from the end of the 1930s, when it seemed more and more likely that war would break out. The image of the mask came to be seen as a symbol of deception, lies and propaganda, especially after 1933 with the rise of the Nazi regime. As the Nazi movement continued to grow and gain power, the figure of the drummer became the symbolic embodiment of the SA, the NSDAP and its propaganda machinery as well as of Adolf Hitler himself. The motif of the Prince of Darkness refers to the demonization of the Nazi regime, Adolf Hitler and his henchmen, in particular shortly before the outbreak of the war as well as during World War Two. ...

As a Jewish artist Hans Feibusch had already been exposed to repressions by the Nazis since 1930. In exile in England from 1933 on he continued to react to this existential threat in his works. The Drummer is reduced to a theatrical pose by means of the empty facemask and flat areas of colouring. The pose is bereft of the hope that the final beat of the instrument can still be averted. "

(Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin: Kassandra: Themes of the Times 1933-1939)

Hans Feibusch

Hans Feibusch, (1898 – 1998)

Hans Feibusch, (1898 – 1998)The Trinity in Glory 1966

Oil mural

29 ft. by 50 ft. (8.8 m by 15.2 m)

St. Alban's, Holborn, London

Hans Feibusch, (1898 – 1998) sculptor and muralist was born into a Jewish family in Frankfurt-on-Main, Germany.

In 1933 he had to flee Germany as a result of the political climate.

He settled in England and became a prolific muralist of churches and cathedrals.

Between 1938 and 1970 he painted 40 murals included those at St Alban the Martyr in London, Chichester Cathedral and Goring Church in Sussex

He had converted to Christianity in 1965.But towards the end of his life, haunted and influenced by the tragedy of the Jewish experience, he reverted to Judaism. He is buried at Golders Green Jewish cemetery in London.

His work is clearly influenced by Christian baroque art. In his book on mural painting he describes the deep influence that baroque art had on him.

Bishop George Bell, the Anglican Bishop of Chichester, was a good friend of Hans Feibusch and there resulted a succession of Chichester commissions executed by Feibusch after 1939, including a controversial commision at a Church in Goring by Sea.

In his book, Mural Painting (1946), Feibusch wrote that " the interest in mural painting is reviving amongst architects, painters and the public ; the hopes for a great art to rise up again are higher than they have been for the last 150 years ".

If there was a revival in Britain of mural painting after 1946, much credit must go to Feibusch and Bishop Bell.

Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961Screen design - Adam and Eve 1913-1914

Graphite, oil on paper

Height: 35.6 cm; Width: 50.8 cm

Inscripted, pen, upper right, verso, for wall dec.? by Vanessa Bell?/ prob. not carried out. -

The Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961The Duomo In Lucca c. 1949

Oil on canvas, framed, signed with initials on the back, 44.5 cm x 37 cm

The Charleston Trust, Charleston, Firle, Lewes

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961Study for the Marriage at Cana, circa 1940,

Gouache on board, unframed, 102 cm x 76 cm.

The Charleston Trust, Charleston, Firle, Lewes

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961

Vanessa Bell 1879 - 1961Virgin And Child

Lithograph

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, Christchurch,

New Zealand

Friday, February 13, 2009

Bloomsbury and Berwick

One of the leading members of the Group was Vanessa Bell (née Stephen) (30 May 1879 – 7 April 1961), the sister of the novelist, Virginia Woolf.(1882–1941).

Vanessa Bell is considered one of the major contributors to British portrait drawing and landscape art in the 20th century. After the First World War, she reverted to a more naturalistic style. She had by then begun her close association with Duncan Grant.

During the Second World War, the then Anglican Bishop of Chichester (the celebrated George Bell, Bishop 1929-58) commissioned Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell to provide murals for Berwick Church in Sussex. It is near their home at Charleston, Firle, Lewes.

The Annunciation was one of the murals.

Angelica Bell, daughter of Grant and Bell, was the model for Mary. Bell`s friend, Chattie Salaman posed for the angel Gabriel. The walled garden with its ordered beds behind is based on that at Charleston Farmhouse

On 10th October 1943, Bishop Bell said this in his sermon:

"The work of the artists, their imagination and their painting, is a work of praise. With their hearts they are saying it -with their colour and their brushes -‘ We praise Thee, O God: we acknowledge Thee to be the Lord’.

The very walls with this new glory on them are singing their praises - and we in the congregation - clergy and people - with our hearts attuned with the subject painted and that the artist created, are stirred afresh and exalted to new heights of adoration as we take our place in the great chorus of praise lifted to the Creator by all creation - man and nature -all that is noblest, strongest, wisest, and swiftest, in heaven and on earth.

‘Every created thing which is in the heaven and on the earth and under the earth and in the sea -all things that are in them - heard we saying ‘Unto Him that sitteth upon the Throne and unto the Lamb be blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, for ever and ever.’’

Bishop Bell expressed his belief that the murals represented a fulfilment of his vision to reunite religion and 'modern' art and so bring about a ‘spiritual awakening of our country’.

For the Berwick Church website and more information about the murals see here.

Vanessa Bell (1879 – 1961)

Vanessa Bell (1879 – 1961)The Annunciation 1941-2

Mural

Berwick Church

Vanessa Bell (1879 – 1961)

Vanessa Bell (1879 – 1961)Study for The Annunciation 1940-2

Vanessa Bell painting The Annunciation onto plasterboards at Charleston

Vanessa Bell painting The Annunciation onto plasterboards at Charleston Chattie Salaman and Angelica Bell posing in costume for the Berwick Church murals.

Chattie Salaman and Angelica Bell posing in costume for the Berwick Church murals. Page from Vanessa Bell's photograph album with photographs of her friend Chattie Salaman posing as an angel for the Berwick Church murals

Page from Vanessa Bell's photograph album with photographs of her friend Chattie Salaman posing as an angel for the Berwick Church muralsThe Killing

Michelangelo Buonarroti, (1475-1564)

Michelangelo Buonarroti, (1475-1564)Christ on the cross

Graphite on paper

Height: 42.5 cm; Width: 29.7 cm

Courtauld Institute Art Gallery, London

The Killing

That was the day they killed the Son of God

On a squat hill-top by Jerusalem.

Zion was bare, her children from their maze

Sucked by the dream of curiosity

Clean through the gates. The very halt and blind

Had somehow got themselves up to the hill.

After the ceremonial preparation,

The scourging, nailing, nailing against the wood,

Erection of the main-trees with their burden,

While from the hill rose an orchestral wailing,

They were there at last, high up in the soft spring day.

We watched the writhings, heard the moanings, saw

The three heads turning on their separate axles

Like broken wheels left spinning. Round his head

Was loosely bound a crown of plaited thorn

That hurt at random, stinging temple and brow

As the pain swung into its envious circle.

In front the wreath was gathered in a knot

That as he gazed looked like the last stump left

Of a death-wounded deer's great antlers. Some

Who came to stare grew silent as they looked,

Indignant or sorry. But the hardened old

And the hard-hearted young, although at odds

From the first morning, cursed him with one curse,

Having prayed for a Rabbi or an armed Messiah

And found the Son of God. What use to them

Was a God or a Son of God? Of what avail

For purposes such as theirs? Beside the cross-foot,

Alone, four women stood and did not move

All day. The sun revolved, the shadows wheeled,

The evening fell. His head lay on his breast,

But in his breast they watched his heart move on

By itself alone, accomplishing its journey.

Their taunts grew louder, sharpened by the knowledge

That he was walking in the park of death,

Far from their rage. Yet all grew stale at last,

Spite, curiosity, envy, hate itself.

They waited only for death and death was slow

And came so quietly they scarce could mark it.

They were angry then with death and death's deceit.

I was a stranger, could not read these people

Or this outlandish deity. Did a God

Indeed in dying cross my life that day

By chance, he on his road and I on mine?

Edwin Muir (1887-1959)

Thursday, February 12, 2009

The Good Man in Hell

Peter Howson b.1958

Peter Howson b.1958The Heroic Dosser 1987

Oil on canvas

Size 197.80 x 213.80 cm

The National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

The Good Man in Hell

If a good man were ever housed in Hell

By needful error of the qualities,

Perhaps to prove the rule or shame the devil,

Or speak the truth only a stranger sees,

Would he, surrendering quick to obvious hate,

Fill half eternity with cries and tears,

Or watch beside Hell's little wicket gate

In patience for the first ten thousand years,

Feeling the curse climb slowly to his throat

That, uttered, dooms him to rescindless ill,

Forcing his praying tongue to run by rote,

Eternity entire before him still?

Would he at last, grown faithful in his station,

Kindle a little hope in hopeless Hell,

And sow among the damned doubts of damnation,

Since here someone could live, and live well?

One doubt of evil would bring down such a grace,

Open such a gate, and Eden could enter in,

Hell be a place like any other place,

And love and hate and life and death begin.

Edwin Muir (1887-1959)

An Epiphany on The Annunciation

El Greco. 1541 - 1614

El Greco. 1541 - 1614The Annunciation. about 1597-1600

Oil on canvas.

115 by 67 centimetres,

Museo Thyssen-Bornemesza, Madrid

In his Autobiography, the Scottish poet and the Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University Edwin Muir (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) described the inspiration for the theme of two vivid poems on the theme of The Annunciation. One of the poems is below.

'I remember stopping for a long time one day to look at a little plaque on the wall of a house in the Via degli Artisti [Rome], representing the Annunciation. An angel and a young girl, their bodies inclined towards each other, their knees bent as if they were overcome by love, 'tutto tremante', gazed upon each other like Dante's pair; and that representation of a human love so intense that it could not reach farther seemed the perfect earthly symbol of the love that passes understanding.'

If one looks up Google Maps, and types in "Via degli Artisti [Rome]" one can see photographs of the entire length of the street.

From the look of the photographs, it is a quiet nondescript street, the sort that one would quickly walk through.

Not the sort of place that one could imagine being struck by a sudden epiphany

One does wonder if the small plaque is still there.

The angel and the girl are met,

Earth was the only meeting place,

For the embodied never yet

Travelled beyond the shore of space.

The eternal spirits in freedom go.

See, they have come together, see,

While the destroying minutes flow,

Each reflects the other's face

Till heaven in hers and earth in his

Shine steady there. He's come to her

From far beyond the farthest star,

Feathered through time. Immediacy

of strangest strangeness is the bliss

That from their limbs all movement takes.

Yet the increasing rapture brings

So great a wonder that it makes

Each feather tremble on his wings.

Outside the window footsteps fall

Into the ordinary day

And with the sun along the wall

Pursue their unreturning way

That was ordained in eternity.

Sound's perpetual roundabout

Rolls its numbered octaves out

And hoarsely grinds its battered tune.

But through the endless afternoon

These neither speak nor movement make,

But stare into their deepening trance

As if their gaze would never break.

Edwin Muir (1887-1959)

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Vatican City State

In addition to the official Vatican site which deals with Popes, religion and doctrine, there is also (to my surprise) a separate website for the Vatican City State.

Tomorrow is the eightieth anniversary of the signing of the Lateran accords

There will be a number of "distinctive celebrations" to mark the 80th anniversary of the city-state’s founding.

The first picture (above) depicts the first stamp printed by the new state in 1929.

The stamps for the 80th anniversary (above) depict the Popes from 1929 to today

Monday, February 09, 2009

A Little Angel

Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (1494-1540), known as Rosso Fiorentino

Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (1494-1540), known as Rosso FiorentinoMusician Angel

c. 1520

Tempera on wood, 47 x 39 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

This painting, probably part of a larger work comes from the mature part of Rosso Fiorentino`s career.

In 1605 the picture was placed in the Tribune (la Tribuna) beside the more precious masterworks the Medici family had collected.

Sunday, February 08, 2009

The Martyrdom of St Agatha

Sebastiano Luciani known as Sebastiano del Piombo (c. 1485, Venice – June 21, 1547, Rome)

Sebastiano Luciani known as Sebastiano del Piombo (c. 1485, Venice – June 21, 1547, Rome)The Martyrdom of St Agatha 1520

Oil on canvas 131 x 175cm

Galería Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence

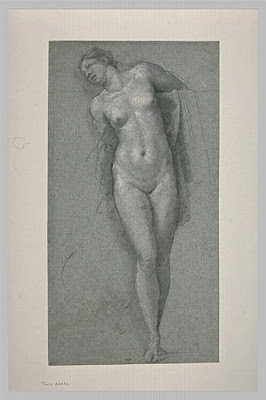

Sebastiano Luciani known as Sebastiano del Piombo (c. 1485, Venice – June 21, 1547, Rome)

Sebastiano Luciani known as Sebastiano del Piombo (c. 1485, Venice – June 21, 1547, Rome)Femme nue, debout, les bras derrière le dos, la tête inclinée à gauche

Initial drawing for St Agatha

Black and white stone on paper

0.353m x 0.188m

Musée du Louvre département des Arts graphiques, Paris

Earlier this week was the Feast of St Agatha, martyr.

The life of St Agatha is told here.

This is one of the most famous paintings of the martyrdom of St Agatha.

Saint Agatha was martyred in the town of Catania in Sicily in the mid-third century. The mountain in the distant landscape at centre left perhaps refers to the legend that Etna erupted on Agatha's death; the city below it is most likely Catania.

There is a ledge in the foreground of the image, which bears the artist`s signature and the date--SEBASTIANUS VENETUS FACIEBAT ROME MDXX--a common device for this type of work, recalling the entrance to a tomb.

It was commissioned by Cardinal Ercole Rangoni (ca. 1491-1527), who had been created a cardinal in 1517 by Pope Leo X. His titular church in Rome was S. Agata dei Goti. He died in the Sack of Rome.

On 3 July 1517 Pope Leo X created thirty-one new cardinals, a number almost unprecedented in the history of the papacy. Leo took advantage of a plot of several of its members of the College of Cardinals to poison him, not only to inflict exemplary punishments by executing one and imprisoning several others, but also to make a radical change in the college. Ercole Rangoni was a Medici placeman in the College.

A younger son of an elite Modenese family, Rangone had been brought to Rome in the train of Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici in 1512

Cardinal Giulio de' Medici (later Pope Clement VII), paid for Saint Agatha, presumably as a gift to his friend and client, Ercole Rangoni

Some have wondered that the drawing was made after a female model, other have proposed that it is an imaginative reconstruction of an antique torso.

There are clear signs from the picturer that the female figure portrayed is meant to be as beautiful and erotically desirable as the Venus sculpture it mimics.

The facial type of Sebastiano's Saint Agatha was in vogue in Rome at the time. It is the probable representation of a contemporary woman in the guise of a saint, presented semi-naked in the pose of a fragment of a classical sculpture of Venus

It is clearly documented that at this time there was a problem calling up lascivious rather than pious desire in the viewer through images of beautiful saints.

It was against paintings such as these that the reformers in the Council of Trent railed and acted against. In 1563, the Council of Trent ruled that in religious images, "figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust."

The reformers were not exercising a prudish dislike of nudity, but were consciously rejecting a new genre of image, one that deliberately, and intentionally, exploited equivocal--and sometimes contradictory--social notions about flesh, sexuality, and spirituality

Saturday, February 07, 2009

The Calumny of Apelles

Alessandro Botticelli. (March 1, 1445 – May 17, 1510)

Alessandro Botticelli. (March 1, 1445 – May 17, 1510)La Calunnia di Apelle/ The Calumny of Apelles. c.1494-1495.

Tempera on panel.

62 × 91 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

An innocent young man is dragged before the king's throne by the personifications of Calumny, Malice, Fraud and Envy. They are followed to one side by Remorse as an old woman, turning to face the naked Truth. Truth, like the innocent youth, is naked as she has nothing to conceal

Apelles of Kos (flourished 4th century BC) was a renowned painter of ancient Greece.

Pliny the Elder rated him superior to preceding and subsequent artists. He dated Apelles to the 112th Olympiad (332-329 BC).

He continues to be regarded as the greatest painter of antiquity

His works have not survived.

One of his most famous paintings was The Calumny.

Apelles produced his painting because he was unjustly slandered by a jealous artistic rival, Antiphilos, who accused him in front of the gullible king of Egypt, Ptolemy I Soter, of being an accomplice in a conspiracy.

After Apelles had been proven to be innocent, he dealt with his rage and desire for revenge by painting the picture

Several Italian Renaissance painters repeated his subjects including this one. Such works illustrate the admiration felt by Renaissance artists for Antiquity, as well as their desire to rival the achievements of their illustrious forebears

See Wikipedia under Calumny of Apelles (Botticelli) for a full description and commentary.

"Botticelli based his figure of Truth on the classical type of the Venus pudica, as well as his own depictions of Venus. She is a naked beauty, an effective opposite to the personification of Remorse, an old, grief-stricken woman in threadbare clothes.

Truth, like the innocent youth, is almost naked as she has nothing to conceal. The eloquent gestures and expression of the only towering figure in the painting are pointing up towards heaven, where a higher justice will be meted out.

Rancour, clothed in black, is dragging Calumny forward with his right hand; as a symbol of the lies which she has spread, she is holding a burning torch in her left hand, while she is pulling her victim, an almost naked youth, by the hair behind her with her right hand. His innocence is shown by his nakedness, signifying that he has nothing to hide. In vain has he folded his hands so as to beseech his deliverance.

Behind Calumny, the figures of Fraud and Perfidy are studiously engaged in hypocritically braiding the hair of their mistress with a white ribbon and strewing roses over her head and shoulders. In the deceitful forms of beautiful young women, they are making insidious use of the symbols of purity and innocence to adorn the lies of Calumny.

The king is sitting on the right-hand side of the picture on a raised throne in an open hall decorated with reliefs and sculptures. He is flanked by the allegorical figures of Ignorance and Suspicion, who are eagerly whispering the rumours in his donkey's ears, the latter to be understood as symbolizing his rash and foolish nature.

His eyes are lowered, so as he is unable to see what is happening; he is stretching out his hand searchingly towards Rancour, who is standing before him."

Note also the statues and the friezes.

As regards the statues, the one on the extreme right behind Midas is Judith with the Head of Holofernes. Behind Calumny is either David or Theseus. Other statues include Jupiter and Antiope, as well as Minerva and the Head of the Medusa.

As regards the friezes, behind Truth is the battles of the centaurs. Behind Penitence is the meeting between Ariadn and Bacchus. Behind Midas is a family of centaurs.

Justice is one of the fundamental values in a civilised state.

After the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent in 1492, the Republic of Florence fell into a state of turbulence in its political and social affairs.

Savonarola emerged as the new leader of Florence after the invasion of Florence by Chrales VIII in 1494.

He fell from power in 1498 and was executed in May 23, 1498

Botticelli was a follower of Savonarola. The work completed in 1494-5 reflects the influence of Savonarola on the artist in the turbulence that was Florence.

Calumny has of course been part of life since the Dawn of Time. Opportunities for calumny have multiplied since the Internet.

An excellent essay on the subject by Michael P Orsi was published in The American Spectator on 19th October 2007.

He said:

"[Calumny] presents us with a situation of serious moral and ethical concern because it violates the dignity of persons and undermines truth. And in the end, truth is the only basis on which a good society can be built.

Those involved in [calumny] would do well keep in mind the words of the Prophet Isaiah 33:15, which says of the good person: "He who acts with integrity, who speaks sincerely ...shuts suggestion of murder out of his ears, and closes his eyes against crime, this man will dwell in the heights."

Friday, February 06, 2009

Eloquence saves Innocence from Calumny

GREGORIO LAZZARINI

GREGORIO LAZZARINIVenice 1665 - Villabona, Rovigo 1730

ELOQUENCE RESCUES THE INNOCENT FROM CALUMNY c.1690

Oil on canvas, 148x200 cm.

Private Collection

Vicenzo Canal from Vicenza, described Lazzarini as a tireless worker and an extremely pious and pure man, so much as to feel a deep sense of guilt when he happened to paint nude women at the request of clients.

However the painter achieved a considerable success and was asked to help decorate the most important churches in Venice and the houses of the ancient Venetian nobility (Orpheus and the Bacchantes for the Procurator Correr, now in Cà Rezzonico, 1698).

The subject of the painting - as it is clear in the inscription “Eloquentia a Calumnie furore/ Innocentem libetrat/ Caput....”added on the open volume in the background on the left, below the parrot - is a free interpretation of the very famous allegory of Calumny, painted by the Greek painter Apelle

The theme was popular in the Renaissance period. Botticelli painted a version now in the Uffizi in Florence.

Calumny is represented as a beautiful woman, overcome by passion and anger; in one hand she is holding a flaming torch, in the other one she is dragging by the hair a man who is lifting up his arms, invoking the gods as witnesses.

He represents Innocence, the victim of false accusations, saved by Eloquence who is coming to help him and who is represented as a woman wrapped in a red cloak, accompanied by Cupid holding the caduceus, the sign of Mercury, the god of Eloquence.

Thursday, February 05, 2009

The Beheading of St Paul

Alessandro Algardi (1598 - 1654)

Alessandro Algardi (1598 - 1654)The Beheading of St Paul

c. 1650

Marble, height: 286 cm

San Paolo Maggiore, Bologna

The death of St Paul by beheading is an unusual theme in art. It only occurs infrequently

This sculpture was specially commissioned for the Church of San Paolo Maggiore in Bologna

Of this piece a commentator has written:

"Algardi created a masterpiece without equal in Baroque sculpture. Often compared to painted altarpieces, Algardi's tableau exploits the traditional strength of sculpture by achieving a fully rounded, spatially complex group which plays upon the contrasting types and emotions of the figures.

Having established action frozen in time, the sculptor sets a spiral pattern in motion, from the poised right arm of the executioner through the shoulders and arms of the kneeling saint and back to his assailant's right leg and drapery.

The centre of the composition is a void, and tension builds up because of the imminent execution and the inevitability of martyrdom."

While the rest of the world were engaged in the furore over the lifting of the excommunications of the "Econe Four", the words of Pope Benedict XVI in General Audience on Wednesday, 4 February 2009 were sadly overlooked.

Zenit (but surprisingly not the official Vatican website) reports his words.

The talk was the final talk on the series of talks given by the Pope on the life and works of St Paul, which he had undertaken to commemorate The Year of St Paul.

In his talk, he discussed the death and legacy of St Paul.

""The figure of St. Paul is magnified beyond his earthly life and his death, he has left in fact an extraordinary spiritual heritage," he said. "He as well, as a true disciple of Jesus, became a sign of contradiction."

First he discussed how the Letters of St Paul became part of the Liturgy.

Then how much the writings of St Paul influenced the early Fathers of the Church.

He discussed the importance of St Paul on the life and works of Luther and how Luther`s interpretation "gave him a new, radical confidence in the goodness of God, who pardons everything without condition".

His surprisingly mild words about Luther may indicate the Pope`s rapprochement towards the Lutheran Church especially in Germany.

He then discussed how in reaction to Luther, the Council of Trent attempted a similar synthesis to that attempted by Luther but emerged with a "synthesis between law and Gospel, conforming to the message of sacred Scripture read in its totality and unity" and consistent with Catholic tradition.

He then went on to discuss 19th century developments in the study of St Paul`s writings which emphasised the concept of liberty:

""Here is emphasized as central above all the Pauline thought of the concept of liberty: In this is seen the heart of the thought of Paul, as on the other hand, Luther had already intuited," he said. "Now, nevertheless, the concept of liberty was reinterpreted in the context of modern liberalism.""

Then he discussed more modern developments which because of the shortness of the talk had to be truncated:

""Later, the differentiation between the proclamation of St. Paul and the proclamation of Jesus was strongly emphasized. And St. Paul appears almost as a new founder of Christianity," the Pope noted. "But I would say, without entering here into details, that precisely in the new centrality of Christology and the Paschal mystery, the Kingdom of God is fulfilled, the authentic proclamation of Jesus is made concrete, present, operative."

"We have seen in the preceding catechesis that precisely this Pauline novelty is the deepest fidelity to the proclamation of Jesus,"

He opined that in the last two hundred years that there was an increasing convergence between the Catholic and Protestant views of the teachings of St Paul which bodes well for the cause of ecumenism:

""In the progress of exegesis, above all in the last 200 years, the convergences between Catholic and Protestant exegesis also grow, thus bringing about a notable consensus precisely in the point that was at the origin of the greatest historical dissent," Benedict XVI said. "Therefore a great hope for the cause of ecumenism, so central for the Second Vatican Council.""

He summed up the legacy of St Paul thus:

""Substantially, there remains luminous before us the figure of an extremely fruitful and deep apostle and Christian thinker, from whose closeness, every one of us can benefit," the Pontiff concluded. "To tend toward him, as much to his apostolic example as to his doctrine, would be therefore a stimulus, if not a guarantee, to consolidate the Christian identity of each one of us and for the renewal of the whole Church.""

A wonderful and remarkable talk. It is sad that it has ben overshadowed by other matters.

For those concerned that the Pope will undermine progress in ecumenism and the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, surely a matter for comfort.

For those who regard the Pope as a reactionary and hard-line theologian, perhaps they might be surprised. Hopefully commentators will realise that labels such as "conservative" and "liberal" are redundant and far, far too simplistic when discussing what this particular Pope thinks and teaches

Wednesday, February 04, 2009

Good Samaritan

Jacopo Bassano (also known as Jacopo da Ponte) (1510-1592)

Jacopo Bassano (also known as Jacopo da Ponte) (1510-1592)Study for 'The Good Samaritan' (National Gallery, London) (recto)

probably 1550-70

Chalk (black and red) on paper (blue)

Height: 21.6 cm; Width: 27.4 cm

Inscription

Stamped, ink, recto, collector's mark of Robert Witt, Lugt 2228a:

RMW

The Courtauld Institute, London

Jacopo Bassano (also known as Jacopo da Ponte) (1510-1592)

Jacopo Bassano (also known as Jacopo da Ponte) (1510-1592)The Good Samaritan

probably 1550-70

Oil on canvas

101.5 x 79.4 cm

The National Gallery, London

The distant city is the artist's native Bassano

A traveller tends to the wounds of a total stranger: neighbourly love overcomes racial and religious prejudice.