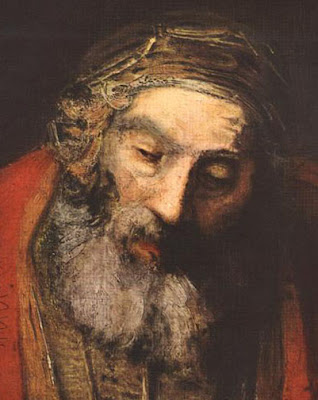

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (July 15, 1606 – October 4, 1669)

The Return of the Prodigal Son

1669

Oil on canvas, 262 x 206 cm

The Hermitage, St. Petersburg

In a review of the book, FORGIVENESS: A philosophical exploration by Charles Griswold (272pp. Cambridge University Press) in the TLS Roger Scruton, Research Professor at the Institute for the Psychological Sciences, Arlington, Virginia asks the question, "What is forgiveness?"

"What is forgiveness, and what good does it do? How are we helped by offering forgiveness and how are we helped by receiving it? Can forgiveness be offered on behalf of another or must it always come from the victim? And is there always a victim?

The crimes of the twentieth century, now receding from human memory with the rapidity that guilt alone can generate, ought to have put those, and similar questions, firmly on the syllabus of anglophone moral philosophy. ...

Christ taught that those who ask forgiveness must also grant it, and enshrined this maxim in the prayer that his disciples repeat each day.

The love-one’s-neighbour idea, which Jews and Christians believe to be the core of morality, is unintelligible without the context of mutual forgiveness. ...

Turning to the world in which we find ourselves, Griswold argues that forgiveness is both a process, whereby two people cope with an injury inflicted by one upon the other, and a virtue. He understands virtue in the Aristotelian way, as a disposition, turned towards the good, and promoting the fulfilment of the person who possesses it.

Virtues are the goal of moral education, and to this extent, Griswold implies, forgiveness can be learned and taught. But some things will remain unforgiven, and in all its occurrences forgiveness should be distinguished from forgetting, condoning or turning away in defeat.

Forgiveness is not achieved unilaterally: it is the result of a dialogue, which may be tacit, but which involves reciprocal communication of an extended and delicate kind. The one who forgives goes out to the one who has injured him, and his gesture involves a changed state of mind, a reorientation towards the other, and a setting aside of resentment.

Such an existential transformation is not always or easily attained, and can only be achieved, Griswold suggests, through an effort of cooperation and sympathy, in which each person strives to set his own interests aside and look on the other from the posture of the “impartial spectator”, as [Adam]Smith described it.

Crucial in this process are the “narratives” which the parties recount to themselves, and Griswold draws interestingly on recent work in “narratology” in his search for the crucial factor in the process of psychic repair. This is the factor that permits a voiding of resentment in the one soul, and a self-giving through contrition in the other.

Each party’s narrative is both an account of the injury, and an allocation of blame; ideal and reality, exoneration and fault, are all woven together, and forgiveness can be seen as in part an attempt to harmonize the narratives, so that the story comes to an end in a new beginning. ...

Those who ask God to forgive them their trespasses are not petitioning an injured party: God cannot be injured. Yet he can forgive us, in the same way that “we forgive those who trespass against us”. We ask God to forgive us in order to restore our relationship with him, and the process may be arduous and long.

Here again, Griswold might have fruitfully studied what has been said about this process in the Catholic tradition – in particular concerning the need for confession, contrition, penitence and atonement, in order to attain that final homecoming into the place of love. Much that Griswold says tracks that process without explicitly acknowledging it. As a result he tends to overlook the enormous part played by penitence in restoring and deepening our affections. ...

But he does not ask the question: what kind of a being is it that can forgive?

Dogs don’t forgive, because dogs don’t resent. Forgiveness is unique to rational beings, and is a gift of metaphysical freedom. Only the accountable being, able to take responsibility for his own actions and mental states, can forgive or be forgiven, and this way of overcoming conflict has next to nothing in common with the peace of the “pecking order”, or the territorial settlements among badgers and bears.

Of course, Griswold is aware of this, and insists on the place of responsibility in the logic of resentment. But at a time when the evolutionary biologists are producing one phoney account after another, designed to show that human societies are constructed from the same ingredients as the tribes of apes, and that “altruism” in people is just a later manifestation of the self-sacrificing instincts of the soldier ant, it is surely a duty of philosophers to point out that interpersonal harmony is achieved through attitudes and virtues that only a free and accountable being could ever exemplify, and that this means that no theory of animal society could ever be generalized to cover us.

The study of forgiveness would be a good starting point from which to roll back the tide of debunking, and show the distinctness and the spiritual richness of the human condition. Of course, that would probably lead away from the “secular” approach that Griswold adheres to. But it would lead in a truthful direction. "

No comments:

Post a Comment