On 21st November 2009 Pope Benedict XVI spoke to an invited audience of artists in the Sistine Chapel. There were about 250 artists present.

It marks the tenth anniversary of Pope John Paul II`s address "Letter to Artists" when he wrote that the Church "needs art."

He also referred to the twenty fifth anniversary of Blessed Fra Angelico as "the patron of artists"

Again he referred to the contribution of Pope Paul VI of the "historic call" of the Church to artists when he apologised for some of the previous attitudes of the Roman Catholic Church towards artists

Art used to have a very close relationship with the Church, which nowadays is not the case.

Interestingly his discourse probably went deeper than either of his two predecessors did in their pronouncements. He discussed the philosophical concept of "Beauty" and its pursuit, referring to Plato, Dostoevsky and Braque. He discussed the concept of "True Beauty" and its pursuit from that of "False Beauty" and its pursuit.

He discussed how Art can take on a religious quality, thereby turning into a path of profound inner reflection and spirituality. He compared the journey of faith and the artist's path as evidenced by religious art.

His quotations from Hans Urs von Balthasar, Simone Weil (was she not one of Pope Paul VI`s favourite authors ?) and Hermann Hesse illustrate the great breadth of vision and learning of this Pope and that his voice is not simply addressed to Catholics and Christians but to all men and women of goodwill.

His discourse and his final offer to artists is a call or invitation to rescue Western civilisation from the present worship and elevation of false values and its sinking into decay and unreality.

His message is complex and profound and well worth further study and debate.

The interest in religious art should not be seen in isolation from the rest of the present Pope`s teaching. In recent weeks he has discussed:

One awaits with interest the forthcoming future dissertations and theses on the aesthetic theory of Pope Benedict XVI

".... Today's event is focused on you, dear and illustrious artists, from different countries, cultures and religions, some of you perhaps remote from the practice of religion, but interested nevertheless in maintaining communication with the Catholic Church, in not reducing the horizons of existence to mere material realities, to a reductive and trivializing vision. You represent the varied world of the arts and so, through you, I would like to convey to all artists my invitation to friendship, dialogue and cooperation.

Some significant anniversaries occur around this time. It is ten years since the Letter to Artists by my venerable Predecessor, the Servant of God Pope John Paul II. For the first time, on the eve of the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, the Pope, who was an artist himself, wrote a Letter to artists, combining the solemnity of a pontifical document with the friendly tone of a conversation among all who, as we read in the initial salutation, "are passionately dedicated to the search for new 'epiphanies' of beauty". Twenty-five years ago the same Pope proclaimed Blessed Fra Angelico the patron of artists, presenting him as a model of perfect harmony between faith and art.

I also recall how on 7 May 1964, forty-five years ago, in this very place, an historic event took place, at the express wish of Pope Paul VI, to confirm the friendship between the Church and the arts. The words that he spoke on that occasion resound once more today under the vault of the Sistine Chapel and touch our hearts and our minds. "We need you," he said. "We need your collaboration in order to carry out our ministry, which consists, as you know, in preaching and rendering accessible and comprehensible to the minds and hearts of our people the things of the spirit, the invisible, the ineffable, the things of God himself. And in this activity ... you are masters. It is your task, your mission, and your art consists in grasping treasures from the heavenly realm of the spirit and clothing them in words, colours, forms -- making them accessible."

So great was Paul VI's esteem for artists that he was moved to use daring expressions. "And if we were deprived of your assistance," he added, "our ministry would become faltering and uncertain, and a special effort would be needed, one might say, to make it artistic, even prophetic. In order to scale the heights of lyrical expression of intuitive beauty, priesthood would have to coincide with art." On that occasion Paul VI made a commitment to "re-establish the friendship between the Church and artists", and he invited artists to make a similar, shared commitment, analyzing seriously and objectively the factors that disturbed this relationship, and assuming individual responsibility, courageously and passionately, for a newer and deeper journey in mutual acquaintance and dialogue in order to arrive at an authentic "renaissance" of art in the context of a new humanism.

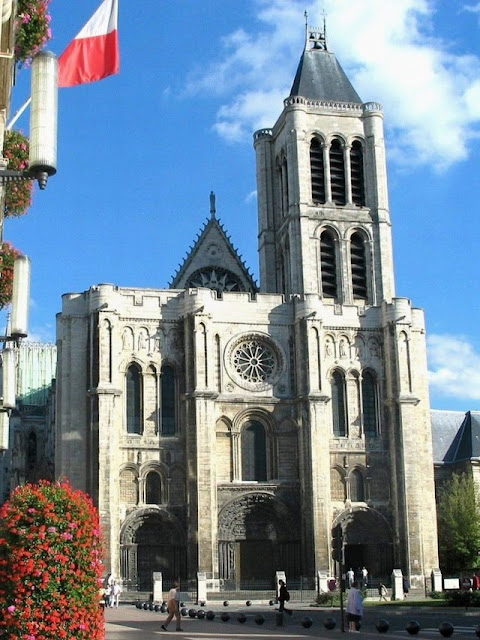

That historic encounter, as I mentioned, took place here in this sanctuary of faith and human creativity. So it is not by chance that we come together in this place, esteemed for its architecture and its symbolism, and above all for the frescoes that make it unique, from the masterpieces of Perugino and Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli, Luca Signorelli and others, to the Genesis scenes and the Last Judgement of Michelangelo Buonarroti, who has given us here one of the most extraordinary creations in the entire history of art. The universal language of music has often been heard here, thanks to the genius of great musicians who have placed their art at the service of the liturgy, assisting the spirit in its ascent towards God. At the same time, the Sistine Chapel is remarkably vibrant with history, since it is the solemn and austere setting of events that mark the history of the Church and of mankind. Here as you know, the College of Cardinals elects the Pope; here it was that I myself, with trepidation but also with absolute trust in the Lord, experienced the privileged moment of my election as Successor of the Apostle Peter.

Dear friends, let us allow these frescoes to speak to us today, drawing us towards the ultimate goal of human history. The Last Judgement, which you see behind me, reminds us that human history is movement and ascent, a continuing tension towards fullness, towards human happiness, towards a horizon that always transcends the present moment even as the two coincide. Yet the dramatic scene portrayed in this fresco also places before our eyes the risk of man's definitive fall, a risk that threatens to engulf him whenever he allows himself to be led astray by the forces of evil. So the fresco issues a strong prophetic cry against evil, against every form of injustice. For believers, though, the Risen Christ is the Way, the Truth and the Life. For his faithful followers, he is the Door through which we are brought to that "face-to-face" vision of God from which limitless, full and definitive happiness flows. Thus Michelangelo presents to our gaze the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End of history, and he invites us to walk the path of life with joy, courage and hope. The dramatic beauty of Michelangelo's painting, its colours and forms, becomes a proclamation of hope, an invitation to raise our gaze to the ultimate horizon.

The profound bond between beauty and hope was the essential content of the evocative Message that Paul VI addressed to artists at the conclusion of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council on 8 December 1965: "To all of you," he proclaimed solemnly, "the Church of the Council declares through our lips: if you are friends of true art, you are our friends!" And he added: "This world in which we live needs beauty in order not to sink into despair. Beauty, like truth, brings joy to the human heart, and is that precious fruit which resists the erosion of time, which unites generations and enables them to be one in admiration. And all this through the work of your hands . . . Remember that you are the custodians of beauty in the world."

Unfortunately, the present time is marked, not only by negative elements in the social and economic sphere, but also by a weakening of hope, by a certain lack of confidence in human relationships, which gives rise to increasing signs of resignation, aggression and despair. The world in which we live runs the risk of being altered beyond recognition because of unwise human actions which, instead of cultivating its beauty, unscrupulously exploit its resources for the advantage of a few and not infrequently disfigure the marvels of nature. What is capable of restoring enthusiasm and confidence, what can encourage the human spirit to rediscover its path, to raise its eyes to the horizon, to dream of a life worthy of its vocation -- if not beauty? Dear friends, as artists you know well that the experience of beauty, beauty that is authentic, not merely transient or artificial, is by no means a supplementary or secondary factor in our search for meaning and happiness; the experience of beauty does not remove us from reality, on the contrary, it leads to a direct encounter with the daily reality of our lives, liberating it from darkness, transfiguring it, making it radiant and beautiful.

Indeed, an essential function of genuine beauty, as emphasized by Plato, is that it gives man a healthy "shock", it draws him out of himself, wrenches him away from resignation and from being content with the humdrum -- it even makes him suffer, piercing him like a dart, but in so doing it "reawakens" him, opening afresh the eyes of his heart and mind, giving him wings, carrying him aloft. Dostoevsky's words that I am about to quote are bold and paradoxical, but they invite reflection. He says this: "Man can live without science, he can live without bread, but without beauty he could no longer live, because there would no longer be anything to do to the world. The whole secret is here, the whole of history is here." The painter Georges Braque echoes this sentiment: "Art is meant to disturb, science reassures." Beauty pulls us up short, but in so doing it reminds us of our final destiny, it sets us back on our path, fills us with new hope, gives us the courage to live to the full the unique gift of life. The quest for beauty that I am describing here is clearly not about escaping into the irrational or into mere aestheticism.

Too often, though, the beauty that is thrust upon us is illusory and deceitful, superficial and blinding, leaving the onlooker dazed; instead of bringing him out of himself and opening him up to horizons of true freedom as it draws him aloft, it imprisons him within himself and further enslaves him, depriving him of hope and joy. It is a seductive but hypocritical beauty that rekindles desire, the will to power, to possess, and to dominate others, it is a beauty which soon turns into its opposite, taking on the guise of indecency, transgression or gratuitous provocation.

Authentic beauty, however, unlocks the yearning of the human heart, the profound desire to know, to love, to go towards the Other, to reach for the Beyond. If we acknowledge that beauty touches us intimately, that it wounds us, that it opens our eyes, then we rediscover the joy of seeing, of being able to grasp the profound meaning of our existence, the Mystery of which we are part; from this Mystery we can draw fullness, happiness, the passion to engage with it every day.

In this regard, Pope John Paul II, in his Letter to Artists, quotes the following verse from a Polish poet, Cyprian Norwid: "Beauty is to enthuse us for work, and work is to raise us up" (note. 3). And later he adds: "In so far as it seeks the beautiful, fruit of an imagination which rises above the everyday, art is by its nature a kind of appeal to the mystery. Even when they explore the darkest depths of the soul or the most unsettling aspects of evil, the artist gives voice in a way to the universal desire for redemption" (no. 10). And in conclusion he states: "Beauty is a key to the mystery and a call to transcendence" (no. 16).

These ideas impel us to take a further step in our reflection. Beauty, whether that of the natural universe or that expressed in art, precisely because it opens up and broadens the horizons of human awareness, pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, can become a path towards the transcendent, towards the ultimate Mystery, towards God.

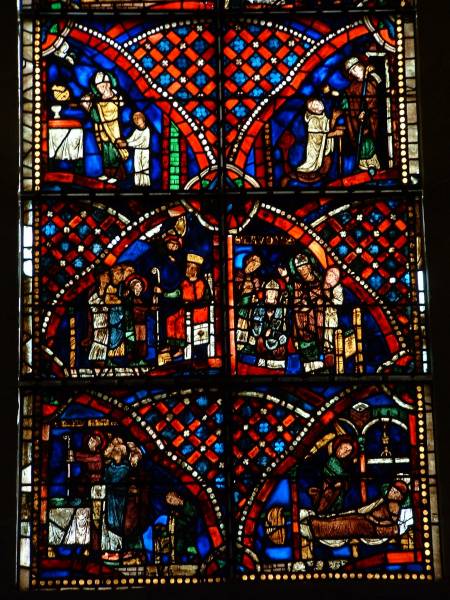

Art, in all its forms, at the point where it encounters the great questions of our existence, the fundamental themes that give life its meaning, can take on a religious quality, thereby turning into a path of profound inner reflection and spirituality. This close proximity, this harmony between the journey of faith and the artist's path is attested by countless artworks that are based upon the personalities, the stories, the symbols of that immense deposit of "figures" -- in the broad sense -- namely the Bible, the Sacred Scriptures. The great biblical narratives, themes, images and parables have inspired innumerable masterpieces in every sector of the arts, just as they have spoken to the hearts of believers in every generation through the works of craftsmanship and folk art, that are no less eloquent and evocative.

In this regard, one may speak of a via pulchritudinis, a path of beauty which is at the same time an artistic and aesthetic journey, a journey of faith, of theological enquiry. The theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar begins his great work entitled The Glory of the Lord -- a Theological Aesthetics with these telling observations: "Beauty is the word with which we shall begin. Beauty is the last word that the thinking intellect dares to speak, because it simply forms a halo, an untouchable crown around the double constellation of the true and the good and their inseparable relation to one another." He then adds: "Beauty is the disinterested one, without which the ancient world refused to understand itself, a word which both imperceptibly and yet unmistakably has bid farewell to our new world, a world of interests, leaving it to its own avarice and sadness. It is no longer loved or fostered even by religion." And he concludes: "We can be sure that whoever sneers at her name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past -- whether he admits it or not -- can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love."

The way of beauty leads us, then, to grasp the Whole in the fragment, the Infinite in the finite, God in the history of humanity.

Simone Weil wrote in this regard: "In all that awakens within us the pure and authentic sentiment of beauty, there, truly, is the presence of God. There is a kind of incarnation of God in the world, of which beauty is the sign. Beauty is the experimental proof that incarnation is possible. For this reason all art of the first order is, by its nature, religious." Hermann Hesse makes the point even more graphically: "Art means: revealing God in everything that exists." Echoing the words of Pope Paul VI, the Servant of God Pope John Paul II restated the Church's desire to renew dialogue and cooperation with artists: "In order to communicate the message entrusted to her by Christ, the Church needs art" (no. 12); but he immediately went on to ask: "Does art need the Church?" -- thereby inviting artists to rediscover a source of fresh and well-founded inspiration in religious experience, in Christian revelation and in the "great codex" that is the Bible.

Dear artists, as I draw to a conclusion, I too would like to make a cordial, friendly and impassioned appeal to you, as did my Predecessor. You are the custodians of beauty: thanks to your talent, you have the opportunity to speak to the heart of humanity, to touch individual and collective sensibilities, to call forth dreams and hopes, to broaden the horizons of knowledge and of human engagement. Be grateful, then, for the gifts you have received and be fully conscious of your great responsibility to communicate beauty, to communicate in and through beauty! Through your art, you yourselves are to be heralds and witnesses of hope for humanity! And do not be afraid to approach the first and last source of beauty, to enter into dialogue with believers, with those who, like yourselves, consider that they are pilgrims in this world and in history towards infinite Beauty! Faith takes nothing away from your genius or your art: on the contrary, it exalts them and nourishes them, it encourages them to cross the threshold and to contemplate with fascination and emotion the ultimate and definitive goal, the sun that does not set, the sun that illumines this present moment and makes it beautiful.

Saint Augustine, who fell in love with beauty and sang its praises, wrote these words as he reflected on man's ultimate destiny, commenting almost ante litteram on the Judgement scene before your eyes today: "Therefore we are to see a certain vision, my brethren, that no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived: a vision surpassing all earthly beauty, whether it be that of gold and silver, woods and fields, sea and sky, sun and moon, or stars and angels. The reason is this: it is the source of all other beauty" (In 1 Ioannis, 4:5).

My wish for all of you, dear artists, is that you may carry this vision in your eyes, in your hands, and in your heart, that it may bring you joy and continue to inspire your fine works. From my heart I bless you and, like Paul VI, I greet you with a single word: arrivederci!

[The Pope greeted the artists in various languages. In English, he said:]

Dear friends, thank you for your presence here today. Let the beauty that you express by your God-given talents always direct the hearts of others to glorify the Creator, the source of all that is good. God's blessings upon you all!"