"For the resolutions of the just depend rather on the grace of God than on their own wisdom; and in Him they always put their trust, whatever they take in hand.

For man proposes, but God disposes; neither is the way of man in his own hands

Pages

Saturday, October 31, 2009

Man proposes, God disposes

Catholic blogosphere: Pontifical Council for Social Communications looks at promoting charity, truth online

"Communications technology keeps changing, but the need to deliver a message with truth and charity is never obsolete, said Italian Archbishop Claudio Maria Celli.

As president of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, Archbishop Celli presided over a four-day meeting of cardinals, bishops and Catholic media professionals to discuss -- mainly in small groups -- new pastoral guidelines for church communications.

A recurring theme during the meeting Oct. 26-29 was what constitutes Catholic communications and what, if anything, can be done about those who use the word Catholic to describe themselves while using all sorts of nasty adjectives to describe anyone who doesn't agree with them.

Archbishop Celli said he didn't think a Catholic bloggers' "code of conduct" would accomplish much, especially when what is really needed is a reflection on what it means to communicate.

Upright, ethical communication is a natural result of a sincere desire to share the truth about God, about faith and about the dignity of the human person, he said.

The archbishop said that what Pope Benedict XVI has said about solidarity and development aid goes for communications as well: "Charity needs truth and truth needs charity."

"Anyone speaking publicly as a Catholic has to have those ethical values that are part of a serious, honest form of communication," Archbishop Celli said.

"In the past, the church's educational efforts included helping people decide what they should or should not watch. Now it must also help them decide what they should or should not produce" and put on the Internet, he said.

Carl A. Anderson, supreme knight of the Knights of Columbus and a consultant to Archbishop Celli's council, said, "If Catholics cannot deal with each other with civility, how can we expect others to?"

"We make certain claims about what kind of community we are; we have set the standards high and we must try really, really hard to live up to that," Anderson said.

He said Pope Benedict is an example of a good Catholic communicator: "He seeks clarity and definition while demonstrating charity and respect for others."

Talking about the Catholic blogosphere, Los Angeles Cardinal Roger M. Mahony said, "I have been appalled by some of the things I've seen; of course, I've been the object of some of them."

Being Christian, he said, means treating others like Jesus treated people: reaching out to all and exercising extreme caution when making judgments.

"One of the side effects of the new technology that frightens me a bit is that people can hide behind a fake facade and then start shooting cannons at other people," the cardinal said.

One of the pontifical council's consultants, Basilian Father Thomas Rosica, the head of Canada's Salt and Light Catholic Media Foundation, said the Internet and blogs have brought about a "radicalization of rhetoric," even among Catholics.

The Web site of Salt and Light Television, he said, sometimes receives hundreds of comments on a story.

"Many we don't publish because of the filth and some we've turned over to the police" because of the threats they contain, he said.

Asked to address the council about Catholic media in North America, Father Rosica said, "On the Internet there is no accountability, no code of ethics and no responsibility for one's words and actions."

So many Web sites and bloggers who call themselves Catholics focus so much on negative stories and messages that increasingly "Christians are known as the people who are against everything," he said.

Cardinal Mahony said the sharp and often uncharitable divisions among Catholics seen on the Internet was particularly pronounced during the 2008 U.S. presidential election campaign.

And, he said, the campaign was not exactly a high point for unity among the U.S. bishops either.

During the campaign, Cardinal Mahony said, "I sensed a dangerous shift away from unity in faith and faith practice to differing opinions on this party or the other party, which I think is a very, very dangerous path to go down."

Some people could get "the impression that some bishops are very much in favor of one political party over the other, which should not be," he said. He added that when it comes to applying the Gospel to social questions bishops should be models for the Catholic faithful on how to hold a civil discussion, online or offline.

"You don't have dialogue when people anonymously throw out their hatreds, their prejudices, their biases and always -- in every case -- end up attacking people," the cardinal said."

Death: Medieval and Modern

"Death was at the centre of life in the Middle Ages in a way that might seem shocking to us today. With high rates of infant mortality, endemic disease, periodic famine, the constant presence of war, and the inability of medicine to deal with commonplace injuries, death was a brutal part of most people's everyday experience. As a result, attitudes towards life were very much shaped by beliefs about death: indeed, according to Christian tradition, the very purpose of life was to prepare for the afterlife by avoiding sin, performing good works, partaking the sacraments appropriately, and adhering to the Church's teachings. Time was measured out in saint's days, which commemorated the days on which the holiest men and women of Christendom had died. Easter, the holiest feast day in the Christian calendar, celebrated the resurrection of Christ from the dead. The landscape was dominated by parish churches - the centre of the medieval community - and the churchyard was the principal burial site

"[It is t]hought to have been made for Anne, Countess of Warwick and daughter of Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick (1382-1439), this is the only illustrated biography of a secular figure to have survived from the late Middle Ages. Richard Beauchamp was a true high-flyer, but his daughter married Richard Neville ('The Kingmaker'), who opposed Edward IV and so caused the exclusion of Anne from all her possessions after his death. It is believed that, to help recover the family's reputation and property, Anne had the 'Pageants' written, probably from an account kept by the family and possibly under the supervision of John Rous (Beauchamp's chantry priest at the Collegiate Church of St Mary's, Warwick), and the extraordinary illustrations made by a Continental artist (known as the Caxton Master) to enhance further the glorifying message.

The Caxton Master marshalled his dramatic skills and ability to create realistic figures for his depiction of Beauchamp's death. Wasted from illness, the dying man receives the last rites from a bishop, while the household is convulsed with sorrow. The lines of the figure at the foot of the bed and the bedcoverings lead the eye to the crucifix held in the centre of the picture and then to the Earl's face, signalling his religious devotion. The artist's ingeniousness comes to the fore also in the way the bed transforms into an exterior tower of the palace in which the scene takes place, further reminding the viewer of the grand status and dignity of the subject."

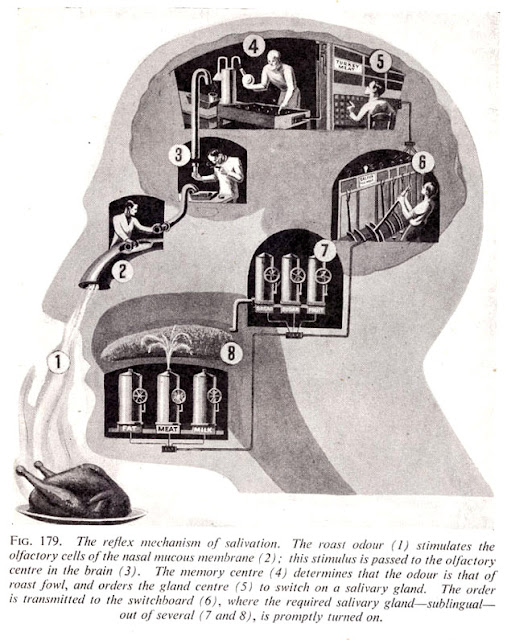

"Fritz Kahn's books and illustrations explored the inner machinery of the human body, using metaphors of modern industrial life. Kahn turned the brain into a complex factory with light projectors, conveyor belts, secretaries and cinema screens; he showed the journeys of blood cells as locomotives encircling the globe; and he compared bones to modern building materials such as reinforced concrete.

Kahn was writing in the 1920s, a period in of great industrial and technological change. The manufacturing industries were achieving incredibly high levels of efficiency thanks to the latest methods of production: factory assembly lines, for example, required only a simple and relatively unskilled input from factory workers. For these workers the body was like a piece of clockwork, its calculated movements acting solely as a functional cog in the social machine.

Technological advancements were bringing many other transformations to the world. A new nature was being constructed. Man could now fly, speak to people on the other side of the world, capture voices and faces that, once preserved, would later seem to be able to bring back the dead. It was an era of great excitement in which people believed that technology had the potential to create a world free from poverty and hardship - a kind of utopia in which machines would protect us from nature's moods, and would provide enough food and protection for all. In fact we were then, and are now, far from fulfilling that dream - but many believe that it is still a possibility for the future."

"259. "Hiding death and its signs" is widespread in contemporary society and prone to the difficulties arising from doctrinal and pastoral error.

Doctors, nurses, and relatives frequently believe that they have a duty to hide the fact of imminent death from the sick who, because of increasing hospitalization, almost always die outside of the home.

It has been frequently said that the great cities of the living have no place for the dead: buildings containing tiny flats cannot house a space in which to hold a vigil for the dead; traffic congestion prevents funeral corteges because they block the traffic; cemeteries, which once surrounded the local church and were truly "holy ground" and indicated the link between Christ and the dead, are now located at some distance outside of the towns and cities, since urban planning no longer includes the provision of cemeteries.

Modern society refuses to accept the "visibility of death", and hence tries to conceal its presence. In some places, recourse is even made to conserving the bodies of the dead by chemical means in an effort to prolong the appearance of life.

The Christian, who must be conscious of and familiar with the idea of death, cannot interiorly accept the phenomenon of the "intolerance of the dead", which deprives the dead of all acceptance in the city of the living. Neither can he refuse to acknowledge the signs of death, especially when intolerance and rejection encourage a flight from reality, or a materialist cosmology, devoid of hope and alien to belief in the death and resurrection of Christ.

The Christian is obliged to oppose all forms of "commercialisation of the dead", which exploit the emotions of the faithful in pursuit of unbridled and shameful commercial profit."

An Allegory of Purgatory

Release of Souls

Friday, October 30, 2009

Purgatory before the Reformation

"The layman, Dante, describes the understanding of the high Medieval Church.

In the final cantos of the Purgatorio, those who desire to be raised to Paradise must first be cleansed of remaining sins by daunting passages through the two rivers flowing from the summit of Mt. Purgatory: the river of forgetfulness (the Lethe) and the river of positive remembrance (the Eunoe).

Dante expressed the best of the Catholic penitential tradition when writing of these double waters: the first, the experience of the forgetting of sin by the sinner; the second, the forgiveness of past sinful events through the ecclesial acceptance by the sinner of God's mercy in the expiatory death of Christ.

Passage through both rivers is necessary for forgiveness. Simply to forget past sins is not enough. The uniquely Christian element in this process, articulated in the coinage of new words with their unheard of prefixes - forgive, perdonare, vergeben, perdonnar, etc. The emphatic, never-seen-before prefixes, pre- for-, emphasize the divine gift to the undeserving.

Embodied, concrete acts by the penitent are necessary for God's such forgiveness. God finally transforms the sinner by the sinner's specific, active acceptance of the divine mercy when performing satisfaction for sin. The penitent is then blessed by the remembrance of that divine transformation together with his or her participation in it."

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Michele Parrasio: Saint Pope Pius V

In Memoriam

The resolution is a vision of Hallam living in God.

"By night we linger'd on the lawn,

For underfoot the herb was dry;

And genial warmth; and o'er the sky

The silvery haze of summer drawn;

And calm that let the tapers burn

Unwavering: not a cricket chirr'd:

The brook alone far-off was heard,

And on the board the fluttering urn:

And bats went round in fragrant skies,

And wheel'd or lit the filmy shapes

That haunt the dusk, with ermine capes

And woolly breasts and beaded eyes;

While now we sang old songs that peal'd

From knoll to knoll, where, couch'd at ease,

The white kine glimmer'd, and the trees

Laid their dark arms about the field.

But when those others, one by one,

Withdrew themselves from me and night,

And in the house light after light

Went out, and I was all alone,

A hunger seized my heart; I read

Of that glad year which once had been,

In those fall'n leaves which kept their green,

The noble letters of the dead:

And strangely on the silence broke

The silent-speaking words, and strange

Was love's dumb cry defying change

To test his worth; and strangely spoke

The faith, the vigour, bold to dwell

On doubts that drive the coward back,

And keen thro' wordy snares to track

Suggestion to her inmost cell.

So word by word, and line by line,

The dead man touch'd me from the past,

And all at once it seem'd at last

The living soul was flash'd on mine,

And mine in this was wound, and whirl'd

About empyreal heights of thought,

And came on that which is, and caught

The deep pulsations of the world,

Æonian music measuring out

The steps of Time—the shocks of Chance—

The blows of Death. At length my trance

Was cancell'd, stricken thro' with doubt.

Vague words! but ah, how hard to frame

In matter-moulded forms of speech,

Or ev'n for intellect to reach

Thro' memory that which I became:

Till now the doubtful dusk reveal'd

The knolls once more where, couch'd at ease,

The white kine glimmer'd, and the trees

Laid their dark arms about the field:

And suck'd from out the distant gloom

A breeze began to tremble o'er

The large leaves of the sycamore,

And fluctuate all the still perfume,

And gathering freshlier overhead,

Rock'd the full-foliaged elms, and swung

The heavy-folded rose, and flung

The lilies to and fro, and said

"The dawn, the dawn," and died away;

And East and West, without a breath,

Mixt their dim lights, like life and death,

To broaden into boundless day. "

"You say, but with no touch of scorn,

Sweet-hearted, you, whose light-blue eyes

Are tender over drowning flies,

You tell me, doubt is Devil-born.

I know not: one indeed I knew

In many a subtle question versed,

Who touch'd a jarring lyre at first,

But ever strove to make it true:

Perplext in faith, but pure in deeds,

At last he beat his music out.

There lives more faith in honest doubt,

Believe me, than in half the creeds.

He fought his doubts and gather'd strength,

He would not make his judgment blind,

He faced the spectres of the mind

And laid them: thus he came at length

To find a stronger faith his own;

And Power was with him in the night,

Which makes the darkness and the light,

And dwells not in the light alone,

But in the darkness and the cloud,

As over Sinaï's peaks of old,

While Israel made their gods of gold,

Altho' the trumpet blew so loud. "

Byzantine All Saints

Monday, October 26, 2009

Saint Francis Kneeling in Meditation

"el mejor pintor deste Santo que se hubiera conocido en este tiempo...porque se conformó mejor con lo que dice la historia” (the best painter of this saint that has been known in this time... because he conformed most fully to that which history tells us). Francisco Pacheco, Arte de la pintura (1649), ed. Bonaventura Bassegoda i Hugas (Madrid: Cátedra, 1990), page 698

"My dear brothers and sisters, what was the life of the converted Francis if not a great act of love? This is revealed by his passionate prayers, rich in contemplation and praise, his tender embrace of the Divine Child at Greccio, his contemplation of the Passion at La Verna, his living "according to the form of the Holy Gospel" (2 Test. 14), his choice of poverty and his quest for Christ in the faces of the poor.

This was his conversion to Christ, to the point that he sought to be "transformed" into him, becoming his total image; and this explains his typical way of life by virtue of which he appears to us to be so modern, even in comparison with the great themes of our time such as the search for peace, the safeguard of nature, the promotion of dialogue among all people. In these things Francis was a true teacher. However, he was so by starting from Christ.

Indeed, Christ is "our peace" (cf. Eph 2: 14). Christ is the very principle of the cosmos, since through him all things were made (cf. Jn 1: 3). Christ is the divine truth, the eternal "Logos", in which, in time, every "dia-logos" finds its ultimate foundation. Francis profoundly embodies this "Christological" truth which is at the root of human existence, the cosmos and history. "

(Pope Benedict XVI Homily at Mass in the Square outside the Lower Basilica of St Francis Sunday, 17 June 2007 on the Eighth Centenary of the Conversion of St Francis of Assisi)

Sunday, October 25, 2009

Benedict XVI: at the Synod, we spoke as pastors

While most of the attention this week was in relation to the announcement about the Anglican Church, the Synod of African Bishops was also taking place in Rome. Here is a talk by Pope Benedict XVI after a meal.

"The term Church - Family of God is no longer just a concept or an idea: it is a living experience of these weeks.

We really were the Family of God are gathered here.

The theme itself was not an easy challenge, with two dangers.

With the help of the Lord, we have done a good job.

This theme: reconciliation, justice and peace certainly implies a strong political dimension but it is clear that reconciliation, justice and peace are not possible without a profound purification of the heart, without a renewal of thought, a metanoia - without the new creation that must come from the encounter with God."

Pope dedicates the general audience to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux

During this week`s General Audience

Saturday, October 24, 2009

The Apostles Saints Jude Thaddaeus and Simon

Domenico Theotokópulos, called El Greco (1541-1614)

Apostle St Thaddeus (Jude)

1610-14

Oil on canvas, 97 x 77 cm

Museo de El Greco, Toledo

Right:

Domenico Theotokópulos, called El Greco (1541-1614)

Apostle St Simon 1610-14

Oil on canvas, 97 x 77 cm

Museo de El Greco, Toledo

Not much is known about these two Apostles.Therefore the following talk by Pope Benedict XVI may be of assistance:

"Today, let us examine two of the Twelve Apostles: Simon the Cananaean and Jude Thaddaeus (not to be confused with Judas Iscariot). Let us look at them together, not only because they are always placed next to each other in the lists of the Twelve (cf. Mt 10: 3, 4; Mk 3: 18; Lk 6: 15; Acts 1: 13), but also because there is very little information about them, apart from the fact that the New Testament Canon preserves one Letter attributed to Jude Thaddaeus.

Simon is given a nickname that varies in the four lists: while Matthew and Mark describe him as a "Cananaean", Luke instead describes him as a "Zealot".

In fact, the two descriptions are equivalent because they mean the same thing: indeed, in Hebrew the verb qanà' means "to be jealous, ardent" and can be said both of God, since he is jealous with regard to his Chosen People (cf. Ex 20: 5), and of men who burn with zeal in serving the one God with unreserved devotion, such as Elijah (cf. I Kgs 19: 10).

Thus, it is highly likely that even if this Simon was not exactly a member of the nationalist movement of Zealots, he was at least marked by passionate attachment to his Jewish identity, hence, for God, his People and divine Law.

If this was the case, Simon was worlds apart from Matthew, who, on the contrary, had an activity behind him as a tax collector that was frowned upon as entirely impure. This shows that Jesus called his disciples and collaborators, without exception, from the most varied social and religious backgrounds.

It was people who interested him, not social classes or labels! And the best thing is that in the group of his followers, despite their differences, they all lived side by side, overcoming imaginable difficulties: indeed, what bound them together was Jesus himself, in whom they all found themselves united with one another.

This is clearly a lesson for us who are often inclined to accentuate differences and even contrasts, forgetting that in Jesus Christ we are given the strength to get the better of our continual conflicts.

Let us also bear in mind that the group of the Twelve is the prefiguration of the Church, where there must be room for all charisms, peoples and races, all human qualities that find their composition and unity in communion with Jesus.

Then with regard to Jude Thaddaeus, this is what tradition has called him, combining two different names: in fact, whereas Matthew and Mark call him simply "Thaddaeus" (Mt 10: 3; Mk 3: 18), Luke calls him "Judas, the son of James" (Lk 6: 16; Acts 1: 13).

The nickname "Thaddaeus" is of uncertain origin and is explained either as coming from the Aramaic, taddà', which means "breast" and would therefore suggest "magnanimous", or as an abbreviation of a Greek name, such as "Teodòro, Teòdoto".

Very little about him has come down to us. John alone mentions a question he addressed to Jesus at the Last Supper: Thaddaeus says to the Lord: "Lord, how is it that you will manifest yourself to us and not to the world?".

This is a very timely question which we also address to the Lord: why did not the Risen One reveal himself to his enemies in his full glory in order to show that it is God who is victorious? Why did he only manifest himself to his disciples? Jesus' answer is mysterious and profound. The Lord says: "If a man loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him" (Jn 14: 22-23).

This means that the Risen One must be seen, must be perceived also by the heart, in a way so that God may take up his abode within us. The Lord does not appear as a thing. He desires to enter our lives, and therefore his manifestation is a manifestation that implies and presupposes an open heart. Only in this way do we see the Risen One.

The paternity of one of those New Testament Letters known as "catholic", since they are not addressed to a specific local Church but intended for a far wider circle, has been attributed to Jude Thaddaeus. Actually, it is addressed "to those who are called, beloved in God the Father and kept for Jesus Christ" (v. 1).

A major concern of this writing is to put Christians on guard against those who make a pretext of God's grace to excuse their own licentiousness and corrupt their brethren with unacceptable teachings, introducing division within the Church "in their dreamings" (v. 8).

This is how Jude defines their doctrine and particular ideas. He even compares them to fallen angels and, mincing no words, says that "they walk in the way of Cain" (v. 11).

Furthermore, he brands them mercilessly as "waterless clouds, carried along by winds; fruitless trees in late autumn, twice dead, uprooted; wild waves of the sea, casting up the foam of their own shame; wandering stars for whom the nether gloom of darkness has been reserved for ever" (vv. 12-13).

Today, perhaps, we are no longer accustomed to using language that is so polemic, yet that tells us something important. In the midst of all the temptations that exist, with all the currents of modern life, we must preserve our faith's identity. Of course, the way of indulgence and dialogue, on which the Second Vatican Council happily set out, should certainly be followed firmly and consistently.

But this path of dialogue, while so necessary, must not make us forget our duty to rethink and to highlight just as forcefully the main and indispensable aspects of our Christian identity. Moreover, it is essential to keep clearly in mind that our identity requires strength, clarity and courage in light of the contradictions of the world in which we live.

Thus, the text of the Letter continues: "But you, beloved" - he is speaking to all of us -, "build yourselves up on your most holy faith; pray in the Holy Spirit; keep yourselves in the love of God; wait for the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ unto eternal life. And convince some, who doubt..." (vv. 20-22).

The Letter ends with these most beautiful words: "To him who is able to keep you from falling and to present you without blemish before the presence of his glory with rejoicing, to the only God, our Saviour through Jesus Christ our Lord, be glory, majesty, dominion and authority, before all time and now and for ever. Amen" (vv. 24-25).

It is easy to see that the author of these lines lived to the full his own faith, to which realities as great as moral integrity and joy, trust and lastly praise belong, since it is all motivated solely by the goodness of our one God and the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore, may both Simon the Cananaean and Jude Thaddeus help us to rediscover the beauty of the Christian faith ever anew and to live it without tiring, knowing how to bear a strong and at the same time peaceful witness to it."

Pope Benedict XVI at a General Audience at Saint Peter's Square Wednesday, 11 October 2006

Baptism

El Greco was commissioned in December 1596 to produce the main retable on The Life of Christ for the church of the Augustinian seminary that became known as the Colegio de Doña Maria de Aragon in Madrid

In July 1601 the finished altar-piece was transported in parts from Toledo to Madrid and assembled.

The altarpiece consisted of at least six religious images from The Life of Christ: The Resurrection, The Crucifixion, The Pentecost, The Baptism of Christ (see above), The Annunciation, and The Adoration of the Shepherds.

After the invasion of the French Napoleonic army in 1808, the paintings were confiscated, removed from the monastery and separated.

Five of the paintings are today in the Prado; the sixth, The Adoration of the Shepherds, is in Bucharest.

It is thought that there may have been a seventh which is now lost.

"[I]t is clear that, through Baptism, the mysterious words spoken by Jesus at the Last Supper become present for you once more. In Baptism, the Lord enters your life through the door of your heart. We no longer stand alongside or in opposition to one another. He passes through all these doors.

This is the reality of Baptism: he, the Risen One, comes; he comes to you and joins his life with yours, drawing you into the open fire of his love. You become one, one with him, and thus one among yourselves. At first this can sound rather abstract and unrealistic. But the more you live the life of the baptized, the more you can experience the truth of these words.

Believers – the baptized – are never truly cut off from one another. Continents, cultures, social structures or even historical distances may separate us. But when we meet, we know one another on the basis of the same Lord, the same faith, the same hope, the same love, which form us. Then we experience that the foundation of our lives is the same. We experience that in our inmost depths we are anchored in the same identity, on the basis of which all our outward differences, however great they may be, become secondary.

Believers are never totally cut off from one another. We are in communion because of our deepest identity: Christ within us. Thus faith is a force for peace and reconciliation in the world: distances between people are overcome, in the Lord we have become close (cf. Eph 2:13).

The Church expresses the inner reality of Baptism as the gift of a new identity through the tangible elements used in the administration of the sacrament.

The fundamental element in Baptism is water; next, in second place, is light, which is used to great effect in the Liturgy of the Easter Vigil....

[I]n the early Church, Baptism was also called the Sacrament of Illumination: God’s light enters into us; thus we ourselves become children of light.

We must not allow this light of truth, that shows us the path, to be extinguished. We must protect it from all the forces that seek to eliminate it so as to cast us back into darkness regarding God and ourselves.

Darkness, at times, can seem comfortable. I can hide, and spend my life asleep. Yet we are not called to darkness, but to light. "

Pope Benedict XVI in his Homily at the Easter Vigil at Saint Peter's Basilica on Holy Saturday, 22 March 2008

How not to regulate worship and liturgy

After Newman left the Church of England to become a Catholic, the Oxford Movement continued in the Church of England.

The so-called "Second Generation" Anglo-Catholics remained in the Anglican Church and began to develop Catholic practices in liturgy and ritual("Ritualism")

From the 1850-1890s several liturgical practices espoused by many Ritualists led to some occasional and intense local controversies.

Those considered most important by adherents of the Catholic movement were known as the "six points":

the use of Eucharistic vestments such as the chasuble, stole, alb and maniple;

the use of a thurible and incense ;

the use of "lights" (especially the practice of putting six candles on the high altar) ;

the use of unleavened (wafer) bread in communion and eastward facing celebration of the Eucharist (when the priest celebrates facing the altar from the same side as the people, i.e. the priest faces east with the people, instead of standing at the "north side" of the "table" placed in the chancel or body of the church, as required by the 1662 Book of Common Prayer) ;

making the sign of the cross ;

the mixing of sacramental wine with water ;

Other contentious practices included:

the use of bells at the elevation of the host;

the use of Catholic terminology such as describing the Eucharist as the "Mass" ;

the use of liturgical processions;

the decoration of churches with statues of saints, pictures of religious scenes and icons ;

the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the practice of the invocation of the saints;

the practice of Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament;

the use of the words of Benedictus at the end of the Sanctus in the eucharistic prayer ; and

the use of the words of the Agnus Dei in the Eucharist

In 1874 the Anglican bishops decided that they had to impose uniformity in worship and uphold the post-Reformation practices.

On 20 April 1874, the then Archbishop of Canterbury introduced into the House of Lords a private members Bill: the Public Worship Regulation Bill.

The Report of the debate in the House of Lords is instructive. It is on the web here.

The intentions of the Archbishop of Canterbury were to help bishops to curb ritualistic practices in the Church more effectively than before.

However, the Bill was taken up by the Government of the day under Benjamin Disraeli. It became a party issue "to put down ritualism".

Through amendments of the Bill by Lord Shaftesbury and the Government, the Bill was altered to provide an effective mechanism to put down Ritualistic practices through a secular court with full powers of a secular court to compel obedience to its orders.

Many clergy were brought to trial and five ultimately imprisoned for contempt of court

In 1888-90, Edward King, Bishop of Lincoln, was prosecuted under the Act

In 1887 Bishop King was denounced as celebrating the Liturgy with practices not permitted by the directives in the Book of Common Prayer and elsewhere governing Anglican worship.

Specifically, the charges were

(1) having lighted candles on the altar;

(2) facing "eastward" (that is, toward the altar and with his back to the congregation) during most prayers;

(3) mixing a little water with the wine in the chalice (done chiefly because the ancients--Jews, Greeks, and Romans alike--regularly diluted their wine with water just before drinking it, but also understood by many as a symbol of human nature being incorporated into the Divine Nature as we are united with Christ through the Sacrament);

(4) using the Agnus Dei ("O Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us") as a hymn just before the receiving of the Holy Communion (this hymn is traditional, but had been omitted from the Book of Common Prayer in 1549 because Cranmer transferred the Gloria to a position at the end of the service, and the words of the Agnus Dei are included in the Gloria, so that it seemed repetitious to have them both within a few minutes of each other);

(5) making the sign of the Cross when blessing the congregation; and

(6) making a ceremony of cleansing the Communion vessels after the service.

None of these practices is particularly controversial today, but they were then thought by some to be signs of inclination to the views--and the company--of the Pope.

King was tried by a Church Court presided over by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The decision of the Court forbade some of these practices, but permitted others while specifying that they had no theological significance. Thus, lighted candles were to be permitted on the altar, but only when needed for purposes of illumination. The Times wrote of the judgement:

"The Ritualists are to have their way in the chief practices Impugned--the other party are diligently assured that there is no such significance as has hitherto been supposed in such practices. The Ritualists...are given the shells they have been fighting for, and the Evangelicals are consoled with the gravest assurances that there were no kernels inside them. "

It was a pragmatic judgement in an attempt to secure peace.

However public outrage grew at the blatant interference in religious matters by secular courts.

In 1906, a Royal Commission effectively nullified the act by admitting that more pluralism in public worship was needed.

For more see:

The Public Worship Regulation Act 1874

Ritualism

Alexander Heriot Mackonochie

Arthur Tooth

T. Pelham Dale

Edward King 1829-1910

Sidney Faithorn Green (who was imprisoned for three years)

.jpg)