Philippe de Champaigne 1602 - 1674

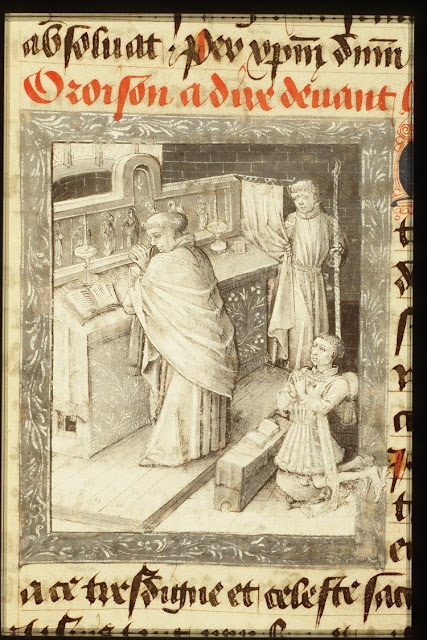

The Vision of St. Juliana (1191-1258) of Mont Cornillon (about 1645/50)

Oil on canvas

15.24 inch x 18.70 inch

The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

It is surprising how often many of the important devotions and feasts of the Catholic Church have been or are initiated or promoted through nuns

Many of the devotions have spread like wild fire. They are picked up and suddenly they spread. There is no calculation. Often the devotion "catches on" long after the originator is dead.

One of them is the devotion for the Feast of Corpus Christi.

It was primarily promoted by the petitions of the thirteenth-century Augustinian nun Juliana of Liège, (also called St. Juliana of Mt. Cornillon) (1193–1252). She was in charge of a leper colony.

She did not promote the idea for personal agrandissement or for political ends. The important thing for her was the spread of the idea. The idea spread despite very strong opposition.

The feast was first celebrated in Liège in 1246, and later adopted for the universal church in 1264.

Here is an extract from The Feast of Corpus Christi by Barbara R. Walters, Vincent Corrigan, Peter T. Ricketts. 2006 The Pennsylvania State University Press. It describes her life and her work in establishing the feast.

"Juliana was born ca. 1192–93 at Retinne, a small village near Liège, the younger of two daughters born to wealthy but non-aristocratic parents. Although their identity is unknown, Mulder-Bakker astutely asserts the plausibility that Juliana’s natural parents were related to the Abbess Imena of Loon or her stepbrother, the archbishop of Cologne, Conrad of Hochstaden, both of whom demonstrated a special and particular protectiveness toward Juliana in her later and more troubled years.

These natural parents of Juliana, in their advancing years, prayed for descendents. Their prayers were answered by the birth of two daughters, Agnes and Juliana ...

The two girls were orphaned at a young age in 1197 and were placed by friends of the family in a newly founded (1176) hospice at Mont Cornillon, along with a gift of approximately 250 hectares of land. Mont Cornillon was located outside Liège, along the route to Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) at the foot of a hill where the Premonstratensians had an abbey.

The house functioned as a leprosarium with four types of residents: men and women suffering from leprosy, and healthy men and women entrusted with various duties in the care of those afflicted. The men and women who provided care were celibate and celebrated the divine office, but were not under religious rule until 1242, when the bishop placed the house under the Rule of Saint Augustine. ...

When Agnes and Juliana were placed at Mont Cornillon, they were immediately moved to an adjacent farm under the care of Sister Sapientia, prioress of the house.

Juliana was a precocious child, mature and gifted in her studies. She mastered French and Latin at an early age and had by adolescence memorized the Psalms, the Song of Songs, and twenty of Saint Bernard’s sermons. Moreover, she routinely displayed the characteristic asceticism, obedience, humility, piety, charity, and eucharistic devotion that typified the religious prototype in the Cistercian vitae of the epoch.

Juliana was also a prophetic and mystical visionary.

In 1210, at age eighteen, her hallmark vision of a full moon with a small fraction missing began.

Through constant prayer she came to interpret this vision as a revelation from Christ. The moon symbolized the Church, and the missing quarter symbolized the absence of a feast day that Christ wanted his faithful to celebrate:

“institutio sacramenti corporis et sanguinis sui quolibet anno semel sollempnius ac specialius recoleretur quam in cena, quando circa lotionem pedem et memoriam passionis sue ecclesia generaliter occupatur”[once every year the institution of the Sacrament of his Body and Blood should be celebrated more solemnly and specifically than it was at the Last Supper, when the Church was generally preoccupied with the washing of the feet and the remembrance of his passion].

After long years of prayers, protest, and revelations from Christ, Juliana embraced as her divinely inspired vocation the task of initiating and promoting the new feast, which should “deinceps per personas humiles promoveri” [from then on be promoted by humble people].

In 1230, after the death of Sapientia, Juliana became prioress, serving under Prior Godfrey, in the episcopacy of the Liège prince-bishop, John of Eppes. She began to confide her vision for the new feast day to her close circle of friends: Eve, an anchoress and recluse at Saint-Martin’s, the collegiate church in Liège; Isabella, a béguine from Huy; and John of Lausanne, the canon at Saint-Martin, who knew the many French theologians and Dominican professors in Liège.

She requested of Canon Dom John that he set her visions of the new feast before his distinguished acquaintances without disclosing her identity. And thus the idea of the new feast day was explained to Jacques of Troyes, archdeacon of Liège, later bishop of the church of Verdun, then Patriarch of Jerusalem, and finally, pope, under the name of Urban IV.

Her idea also was put forward before Hugh of Saint-Cher, Prior Provincial of the Order of the Dominicans, who was later promoted to cardinal of the Church of Rome, and before the most reverend Father Guiard, bishop of Cambrai. Additionally, these matters were shown to the chancellor of Paris, to the friars Gilles, John, and Gerard, who were lectors to the Dominican preachers in Liège, and to many others.

All of these luminaries were of one mind and spirit and could find no reason in divine law that might prohibit the institution of a special feast day celebrating the Sacrament

Juliana was elated by the approbation.

However, she had no erudite or distinguished scholars on whom she could depend to compose the office and Mass for the new feast, and so she chose a young and innocent brother, John, “(q)uem licet in litterarum scientia nosceret imperitum” [although she knew him to be inexperienced in literary matters].

The vita reports that John centonated the office, that is, he employed a process in between rote reproduction from memory and extemporization, which was characteristic of oral transmission, through “the miraculous intervention of the Holy Spirit” while Juliana prayed. When their work was shown to the learned theologians in Liège, it was found theologically perfect and aesthetically pleasing. “Hec autem omnia tante suavitatis et dulcedinis sunt in littera et in cantu, ut etiam a lapideis cordibus devotionem merito debeant extorquere” [And all of the texts and melodies are of such beauty and sweetness that they should be able to wring devotion even from hearts of stone]. ...

After the death of Bishop John of Eppes, the bishopric remained vacant for two years, ultimately resolved by pontifical arbitration in 1240. In the meantime, Prior Godfrey of Mont Cornillon died and was replaced by a Prior [Roger]. The new prior was an enemy of Juliana who allegedly obtained his office through simony, pandered to the bourgeoisie, and befriended those brothers and sisters in the house opposed to her strict enforcement of the religious rule.

He further took advantage of the opportunity afforded by the transition of authority in the bishopric to incite the citizens of Liège to riot by accusing Juliana and several nuns of stealing the charters of the house and diverting funds to bribe the bishop for the institution of the new feast. The townspeople assaulted the monastery and destroyed Juliana’s oratory but did not find the charters, which the nuns had carefully hidden.

Juliana fled to the cell of the recluse, Eve of Saint-Martin, but actually was received into Canon John’s larger residence adjacent to the basilica.

Bishop Robert of Thourette was named successor to John of Eppes by a pontifical council in 1240 but never received the then-customary investiture from Emperor Frederick II. He initiated an inquest at Mont Cornillon and in 1242 deposed the simoniac Prior Roger, ordering him to the leprosarium at Huy.

He installed the young and naïve brother John as prior at Mont Cornillon. Bishop Robert then reinstated Juliana as prioress, had her oratory rebuilt, reconfirmed the religious Rule of Saint Augustine, and excluded the lay citizens of Liège from further participation in the governance of the house.

Following these events, Bishop Robert was introduced to the new feast of Corpus Christi. “[V]iri venerabiles et religiosi sollempnitatis ordinem et processum exposuerunt reverendo patri domino roberto leodiensi episcopo et eidem ut divine munus gratie agnosceret et exaltaret verbis efficacibus suggesserunt”[Venerable religious men set the order and progress of the feast before the reverend father Dom Robert, Bishop of Liège, and effectively persuaded him to acknowledge and exalt the gift of divine grace].

Bishop Robert died at Fosses on 16 October 1246. On his deathbed, in a letter to all clergy, he established the feast for the diocese of Liège on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday.

The letter notes two reasons for instituting the new feast. The first, “to counteract the madness of heretics,” was a rationale later repeated in nearly exact wording by both Hugh of Saint-Cher and Urban IV. The second reason was explained by reference to the saints, whom the Church commemorates every day and yet still honors individually in a yearly feast on their death date. Robert exhorted those around him to love and promote the feast and had them celebrate the new office immediately before his last breath.He concluded his letter with a quote from Matthew 28: 20: “And behold I am with you always, to the end of time.”...

The young Henry of Gueldre, cousin to Count William of Holland and nephew of Duke Henry of Brabant, replaced Bishop Robert of Thourette in 1247, following the death of the latter. Bishop Henry was appointed with the encouragement of the papacy as part of its efforts to secure political support and a suitable successor to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, upon his deposition in 1245.

As bishop, Henry initiated a statute reconfirming the rights of the bourgeoisie in the administration of the house at Mont Cornillon, deposed the young prior John, and brought back the simoniac Roger, who had earlier been sent to Huy by Bishop Robert. The citizens again invaded the monastery and destroyed Juliana’s oratory.

In 1247, Juliana fled Mont Cornillon for a second time with sisters Agnes, Isabella, and Ozile and found refuge in the Cistercian monasteries at Robermont, Val-Benoît, and Val-Notre-Dame. However, the new bishop, Henry, pursued the women, and at each place through cunning machinations prevented their benefactor from extending their stay.

The women departed for Namur, where they initially found shelter among the poor. Their situation came to the attention of Abbess Imène, sister of the most reverend Conrad, archbishop of Cologne, who contacted the reverend John, archdeacon of Liège. The archdeacon procured a house for the women close to the church of Saint Aubain.Abbess Imène also used her connections to obtain annuities from Mont Cornillon commensurate with the considerable inheritances that each had bestowed upon the monastery and took the women under the protection of the monastery.

“Que de consilio peritorum et religiosorum virorum maxime autem reverendi patris Guiardi cameracensis episcopi subiectioni et protectioni prefate abbatisse se quamdiu viverent subdiderunt, ne absque superiore sed solo proprie voluntatis arbitrio vivere dicerentur” [On the advice of experienced religious, especially the reverend father Guiard, Bishop of Cambrai, they submitted to the obedience and protection of the abbess for as long as they lived, lest anyone should say they were living merely at their own whim without a superior].

After the deaths of Agnes and Ozile between 1248 and 1252, Isabella, no doubt influenced by the abbess, persuaded Juliana to move to the larger abbey at Salzinnes; this came under the protection of Cardinal Hugh of Saint-Cher around 1252. After the death of Isabella, Sister Ermentrude from Mont Cornillon later was persuaded to join her there. But the house at Salzinnes was dispersed in 1256, after a furious revolt on the part of the townspeople of Namur against a certain Empress Marie, who managed the county of Namur in the absence of her husband between 1253 and 1256. ...

Upon the dispersal of the abbey at Salzinnes, the abbess took Juliana to the house of a cantor at the Cisterican abbey at Fosses. The cantor provided Juliana with a cell, initially built for a recluse who had recently died. Juliana remained there until her death on 5 April 1258.

On her deathbed she asked for her confessor, John of Lausanne, the canon at Saint- Martin’s. “Desiderabat autem illum ea specialiter ut creditur intentione, ut secreta sua que tantopere in vita celaverat eidem vel in vite sue termino revelaret” [I believe she wanted him specifically so that at the end of her life, she could reveal the secrets she had hidden so long]. Neither he nor any of her friends from Liège came, and so these secrets, perhaps concerning her work on the feast, remain unknown.

The cantor of Fosses administered the last rites to her immediately before her death, and a sacrifice for the dead was offered the next day in the Fosses church. Then, in accordance with Juliana’s wishes, her friend, the monk Gobert d’Aspremont, moved her body by carriage to the Cistercian monastery at Villers. On the following Sunday, an unknown priest arrived and gave an eloquent sermon on the Sacrament, after which Juliana was buried in the section of the cemetery at Villers reserved for saints.

Her cult developed immediately, although it did not receive official recognition until 1869, under Pius IX."

-of-Mont-Cornillon.jpg)